Review of the Papyrological Editor of Papyri.info

by Despina Borcea

I. Introduction: Aim & Outline

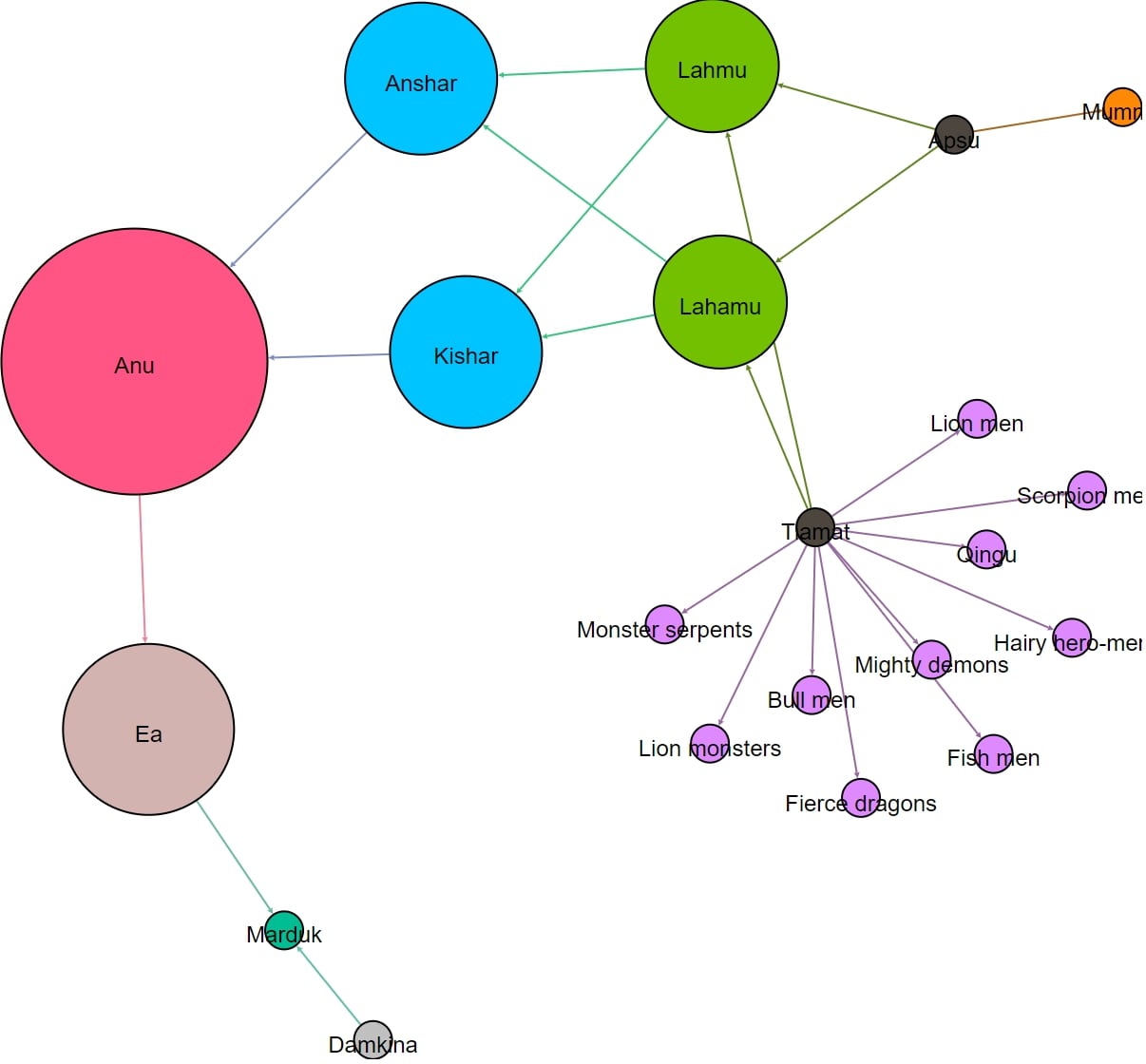

Released in 2010 as a new platform for what was previously three separate papyrological databases, the Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS), the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri (DDbDP) and Heidelberger Gesamtverzeichnis der griechischen Papyrusurkunden Ägyptens (HGV), Papyri.info represents a papyrological research tool with two main functions: to access collections of non-literary texts via its Papyrological Navigator (PN) interface, and to edit such entries and their apparatus criticus according to relevant critical editions via the Papyrological Editor (PE). This review is based on a project designed to encode editorial corrections on several papyri in Leiden+ using the Papyri.info Papyrological Editor (PE) as an instrument, which I encountered while undertaking a module on Digital Classics taught via the SunoikisisDC programme at the Institute of Classical Studies as part of the UCL MA in Classics (2021). The review is intended to assess the usability and accessibility of the PE’s user interface in relation to the general function of the PE model based on the project and its results.

II. Methodology

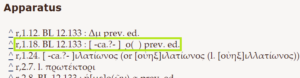

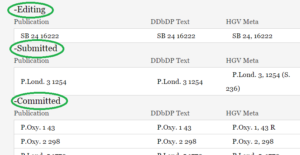

The first phase of the project was to identify the necessary changes to make in the apparatus criticus of several papyri: for this project, 20 corrections to-be-made were allocated (an example below), taken from The Son of Suda Online (SoSOL) “Editing Assignments” Spreadsheet and applied to the texts. The spreadsheet was used to track both authorship as well as progress status of submissions (see below).

When opening the digital version of a papyrus in the Leiden+ format of the Papyrological Editor, the interface also offers the option to open and download the XML file of the document:

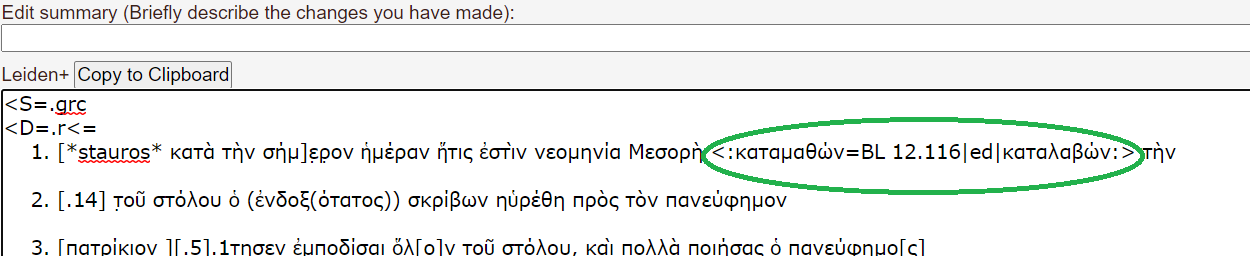

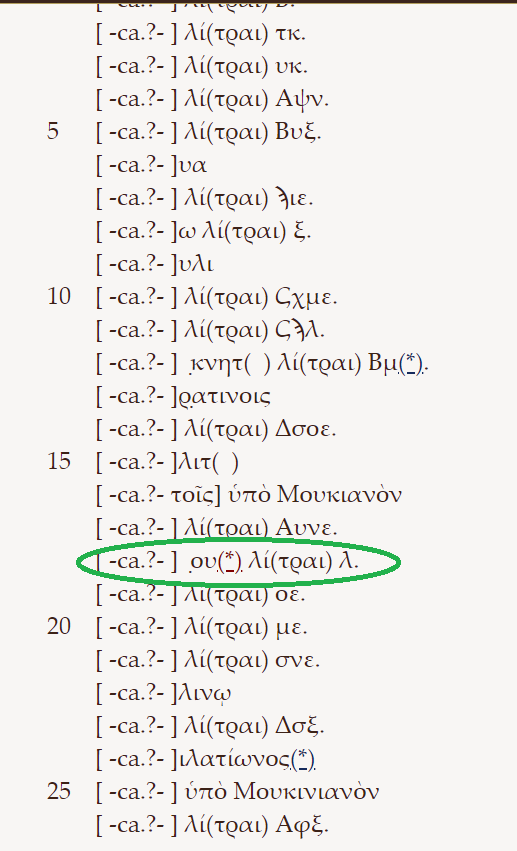

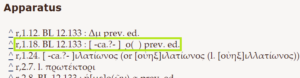

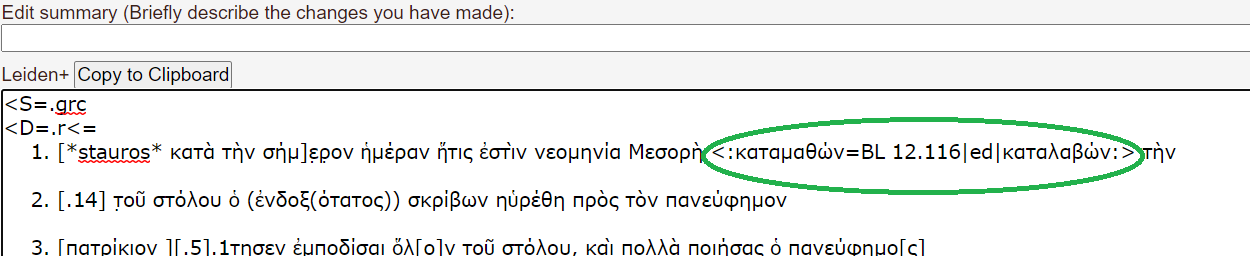

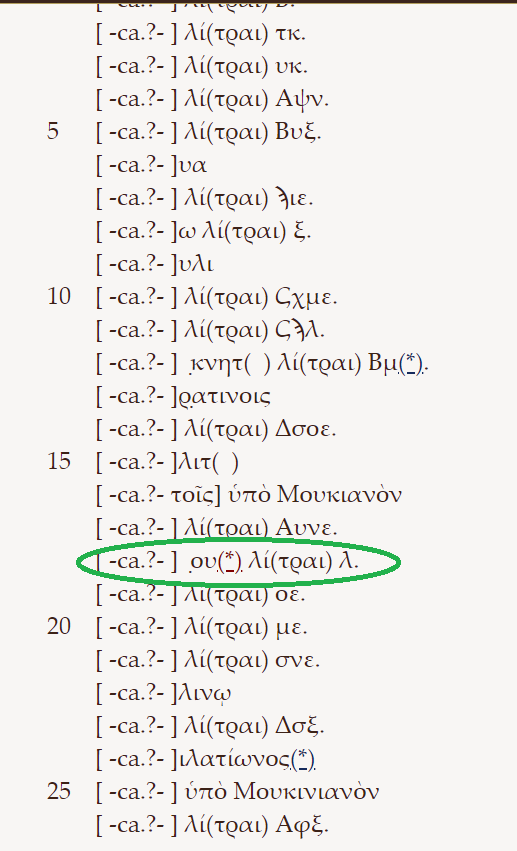

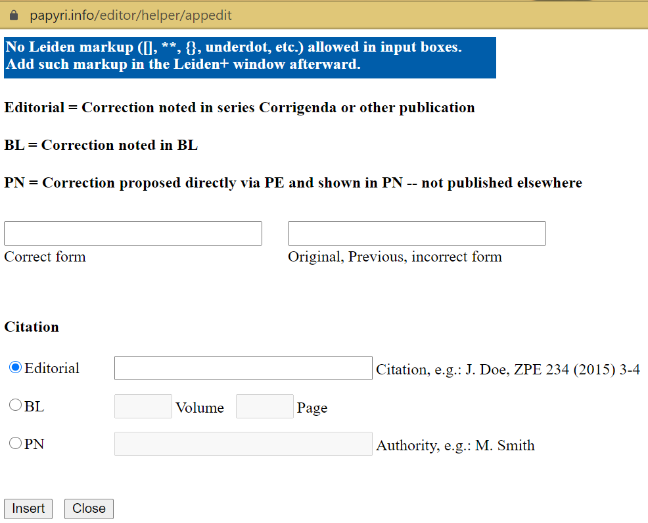

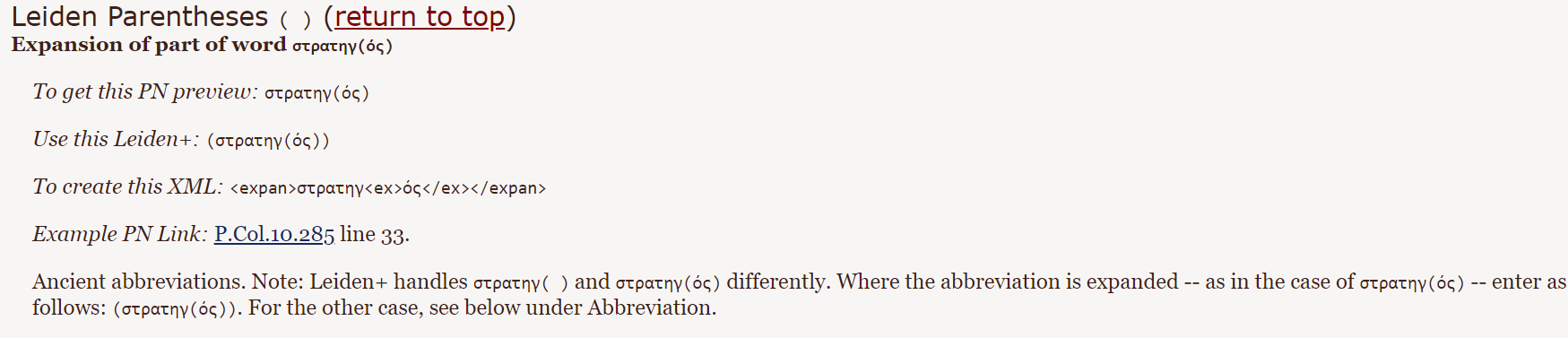

Except for one editorial decision, as to how to expand an abbreviation, all other submissions were either corrections or additions to the apparatus criticus of a papyrus, according to newer editions, as specified on the SoSOL spreadsheet. The changes varied, within the boundaries of editorial corrections to a published document, from supplying and defining numerical values to expanding abbreviations. The figure below shows an example of an editorial correction:

Following the completion of the edits, the changes made were described in brief commentaries, which were submitted for publication simultaneously. The observations shown below describe such changes, alongside other clarifications regarding the digital version not corresponding with the variant on the SoSOL spreadsheet; (as G. Bodard pointed out to me) the online DDB reporting the correction has expanded the abbreviation, whilst the print edition in the BL did not feel the need to:

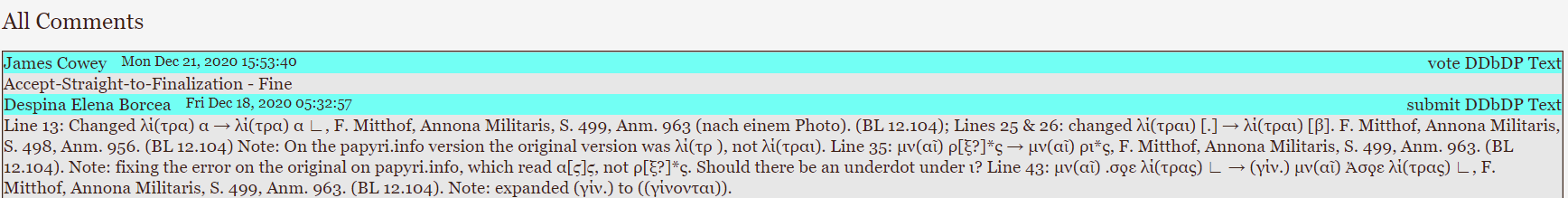

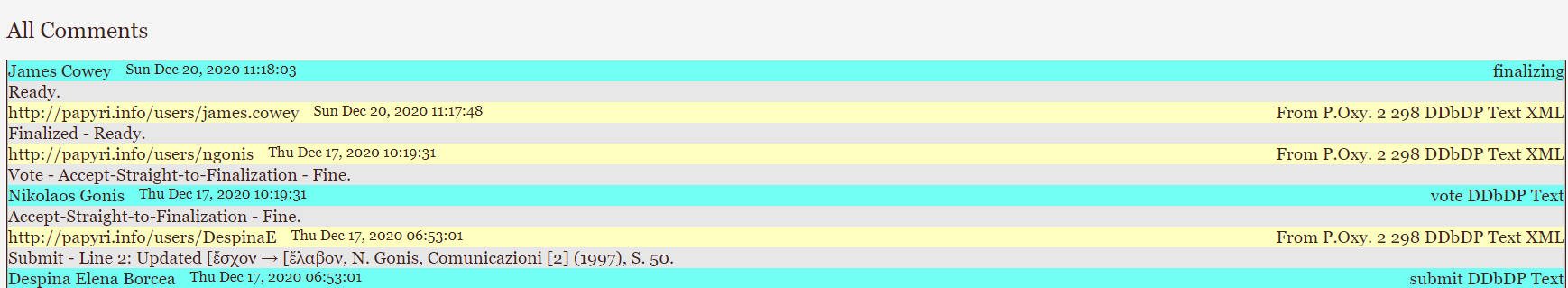

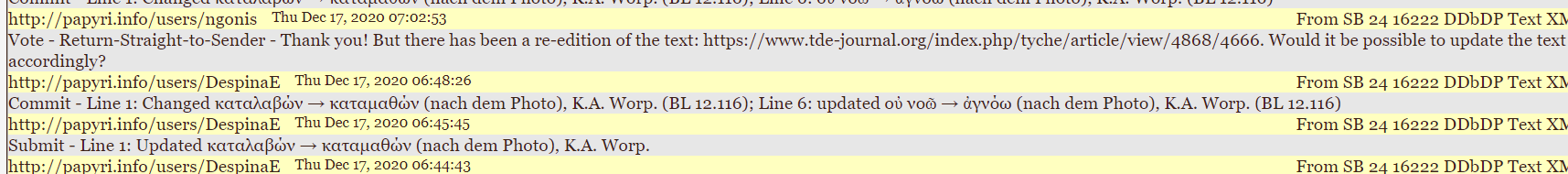

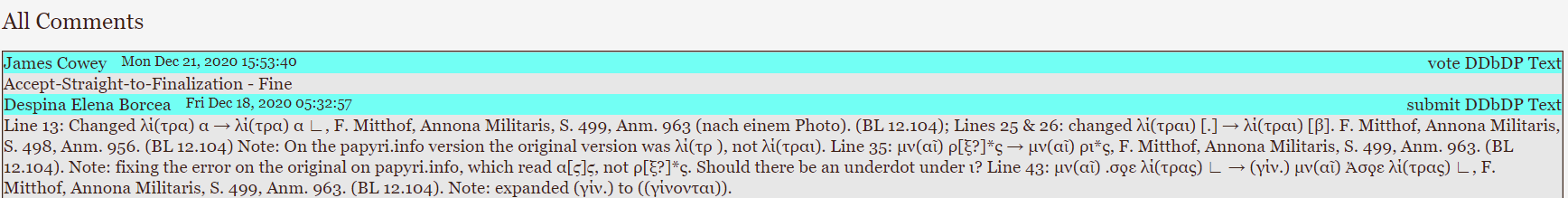

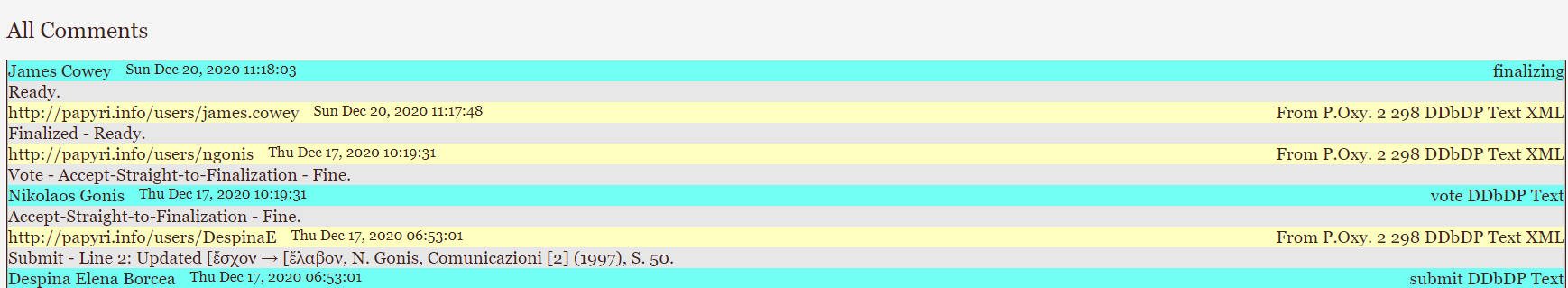

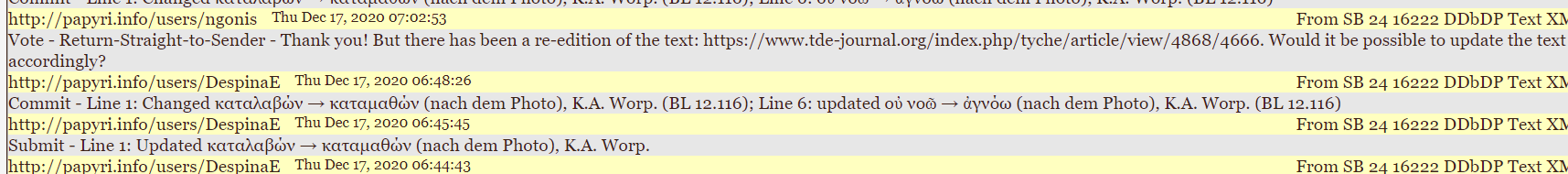

Finally, the editorial board decided on publishing or vetoing the changes and returned with feedback in both cases. The comments are conveniently accessible via the ‘See All comments’ section of a papyrus presentation page. An example is provided below:

Regarding the progress of the project, my expectations of operating with Leiden+ were not only met, but exceeded by the results. In terms of publication, all corrections made before the set deadline were published, with the exception of those on P.Lond. 3 1254. The modifications on the latter were vetoed not due to errors in the code, but (as N. Gonis observed) because of a more recent re-edition of the text than the one included in the SoSOL spreadsheet. The unambiguous format of Leiden+, strongly resembling the Leiden conventions aided the speed of my code input, which was followed by an extremely prompt feedback timeline. The results were returned with commentaries from the editorial board, as shown in the figure above.

III. Discussion

III.1 Improvable Features

While carrying out the editing , no major faults with the interface accessibility were identified. Thus, the following observations represent potential improvements without which carrying out experiments with similar results would be perfectly possible.

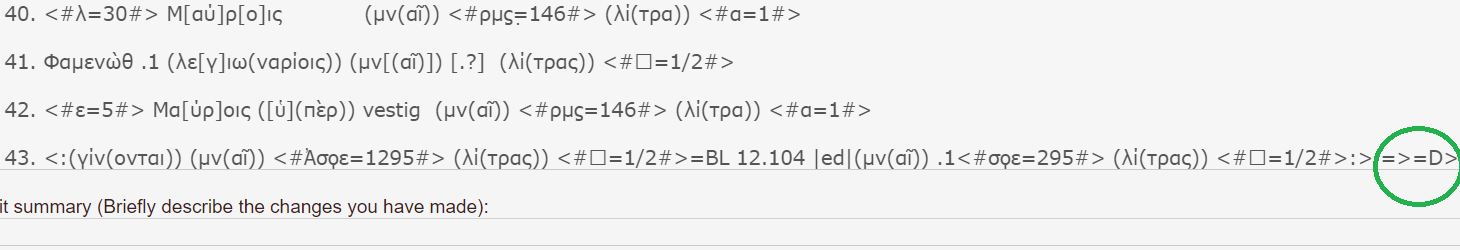

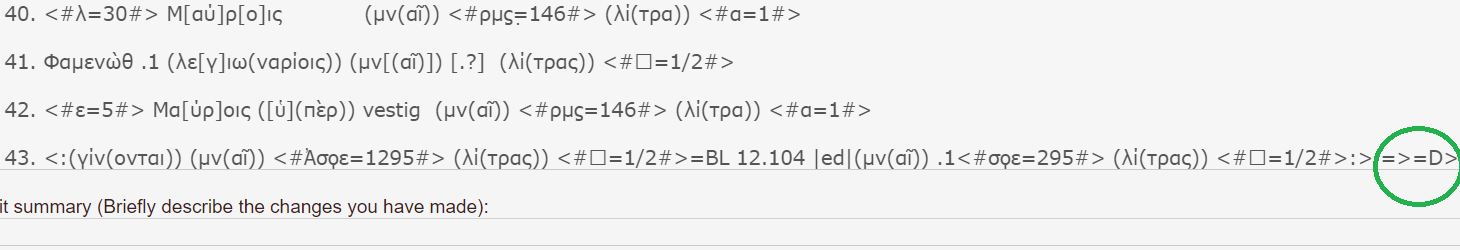

The following two observations concern the visibility of edits on the PE interface. Its potential improvement could render the PE more time efficient. Firstly, while carrying out the experiment, it was observed that there was no method of comparing the proposed draft with the original at the time of editing in the Papyrological Editor. While the ‘Preview’ section proved useful in reviewing the changes made, there was no direct way of examining the edits before saving and previewing them. One example, shown below pertains to P.Lond. 3 1254. Here ‘=>=D>’ was accidentally deleted at the end of the final line (43), but it was not immediately noticeable and thus the PE flagged an error in Leiden+:

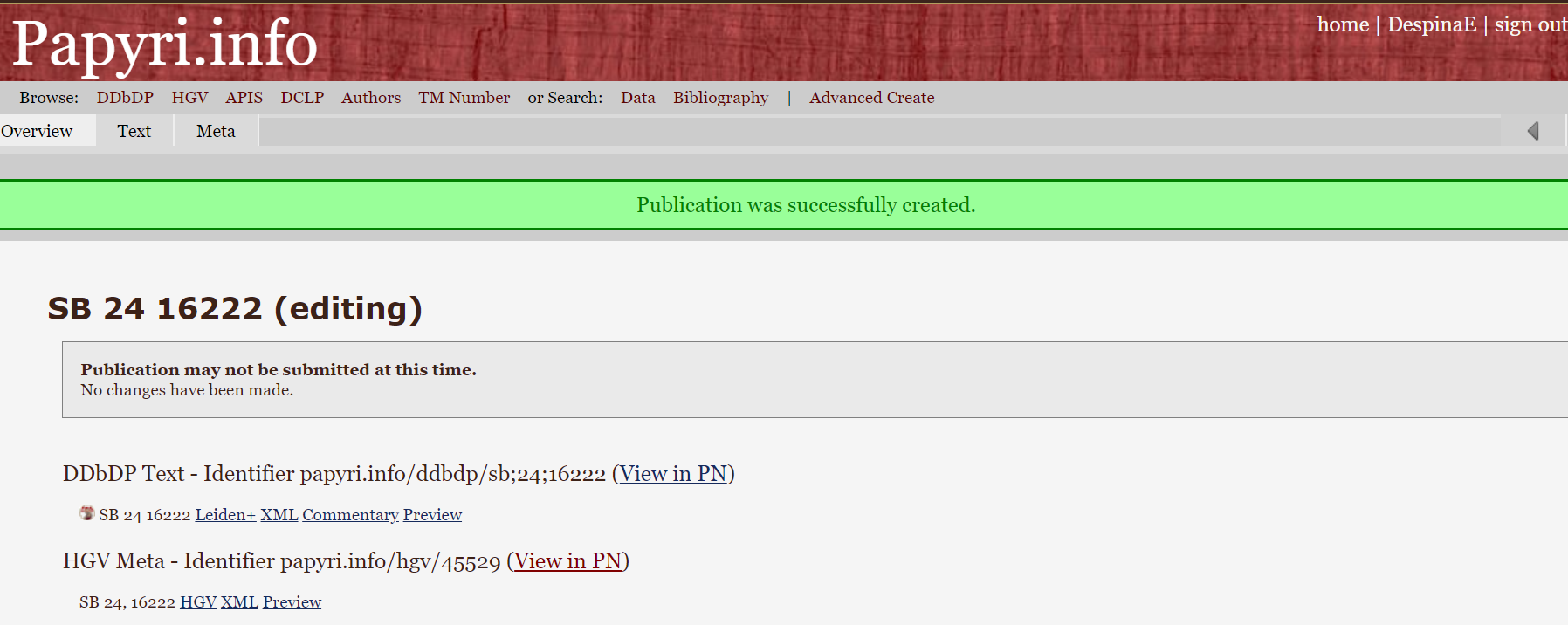

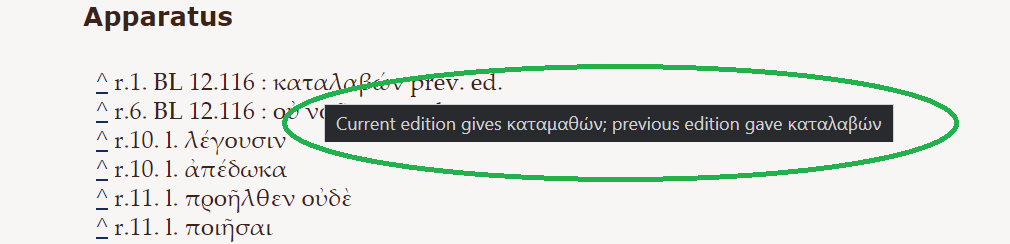

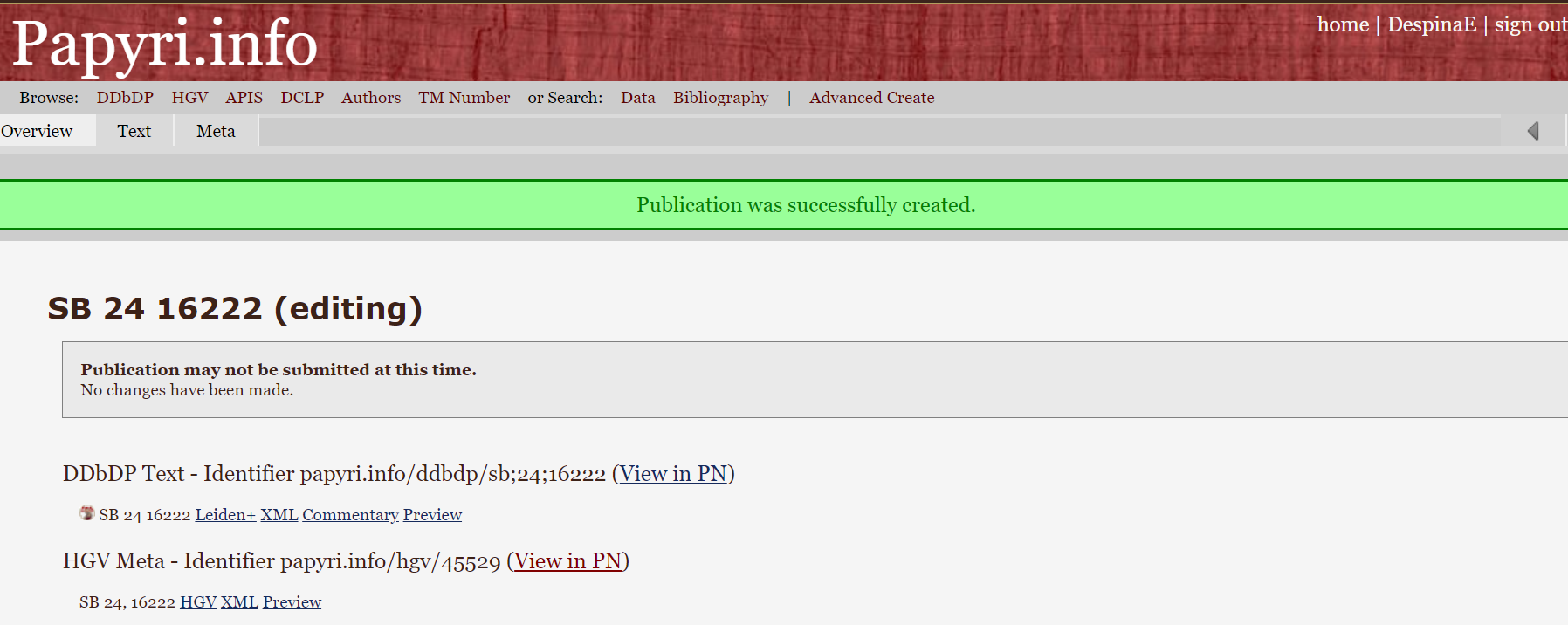

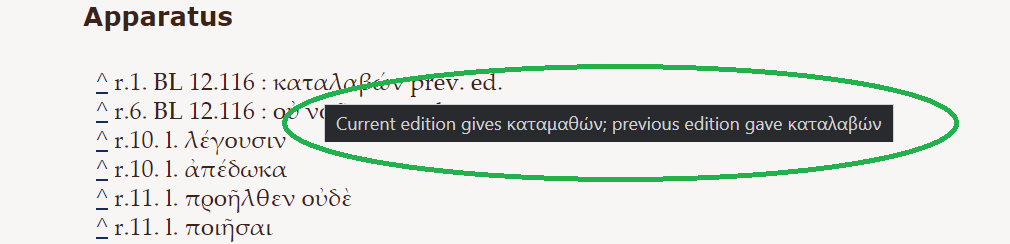

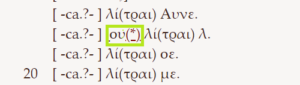

As the correction on line 43 was not the only change made on P.Lond. 3 1254, and the reason for the error was not immediately visible, the entire submission was deleted and restarted from scratch. For efficiency purposes, perhaps it would be useful to have a parallel window next to the PE box to show the original version of the Leiden+ at the time of editing. Alternatively, a pop-up text in the preview showing the original Leiden+ of the line, similar to the message showing when holding the cursor over a footnote in the apparatus criticus (figure below; this screenshot is taken from SB 24.16222, as the edits on P.Lond. 3 1254 were not committed), might make the PE interface less overcrowded than the first suggestion (provided there is a way of efficiently storing the original Leiden+ data).

The second observation regarding the visibility of edits in the Papyrological Editor refers to the ‘Preview’ stage. After saving the amendments on the papyri, they were reviewed prior to their submission to the editorial board. As the length of the papyri varied greatly, it was noted that in the longer texts, the changes in the ‘Preview’ stage were not immediately easy to spot. To illustrate this, P.Oxy. 1 43 is used as an example in fig. below on the left. Because of the extensive nature of both the papyrus and its apparatus criticus, as well as the similarity between specific lines, finding and reviewing the edit in line 18 (highlighted) was moderately confusing. For visibility and efficiency purposes, perhaps it would be advantageous to display the changes made in a colour-coordinated mode between the correction in the text and the note in the apparatus criticus, in addition to the ‘(*)’ at the end of the in-line correction. An example is offered in the two figures below:

III.2 Advantages

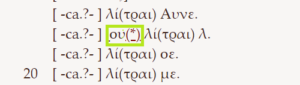

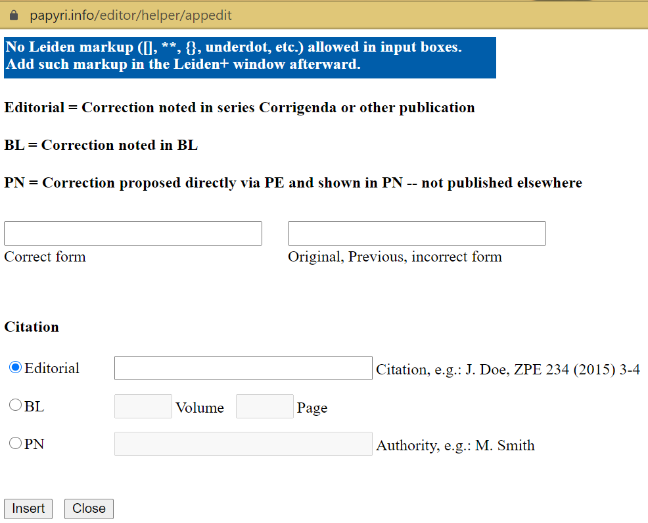

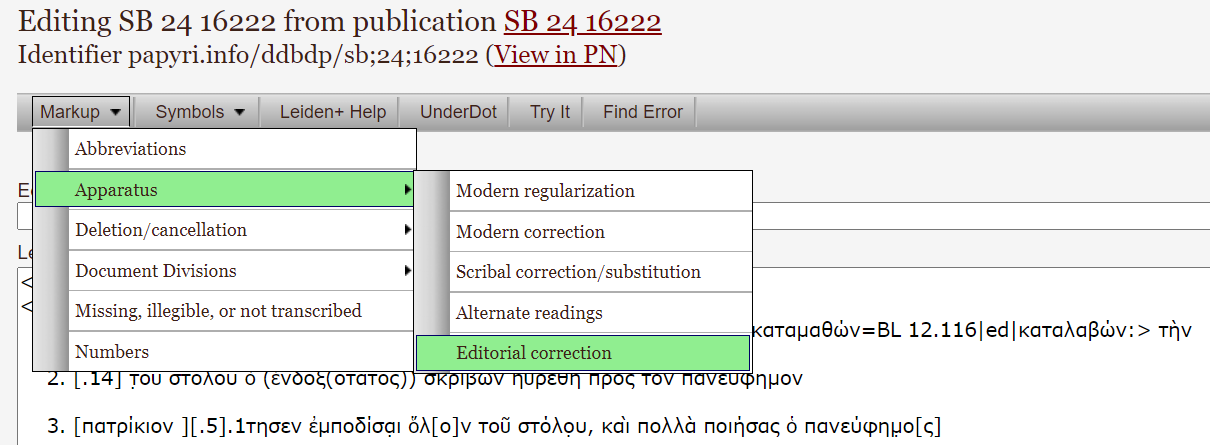

The overall success of the project, in the form of the corrections’ publication, demonstrates the accessibility of the Papyri.info Papyrological Editor. The ease of navigation in PE is realised through several elements. Firstly, the layout of the editorial window in Leiden+ conveniently presents the reviser with a handful of useful instruments, without overcrowding the interface:

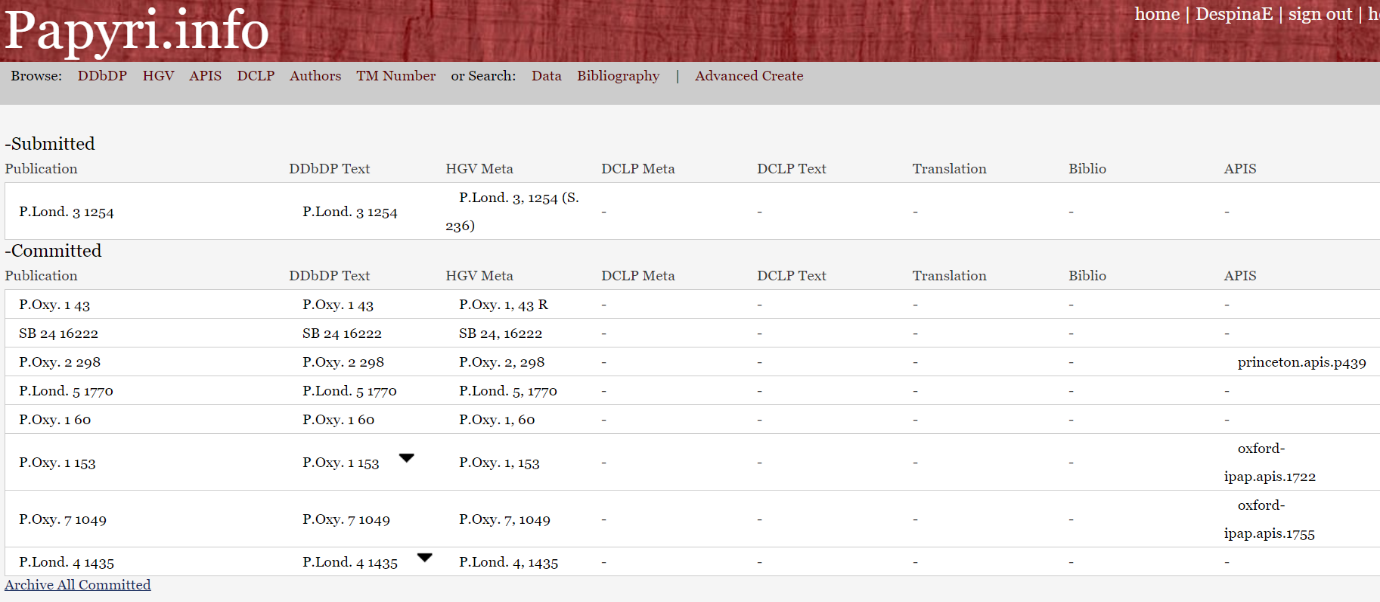

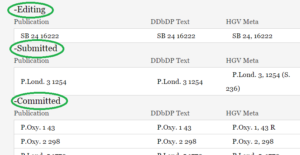

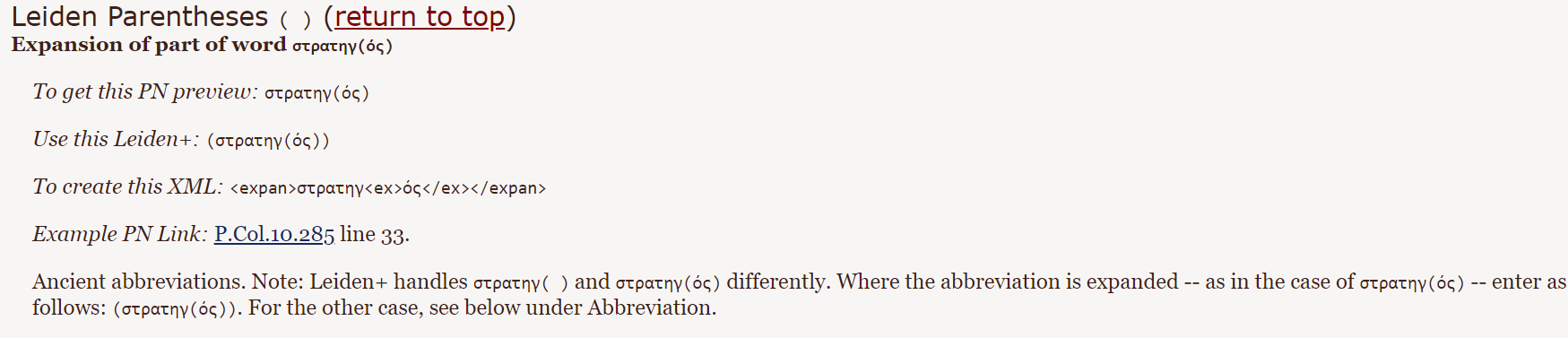

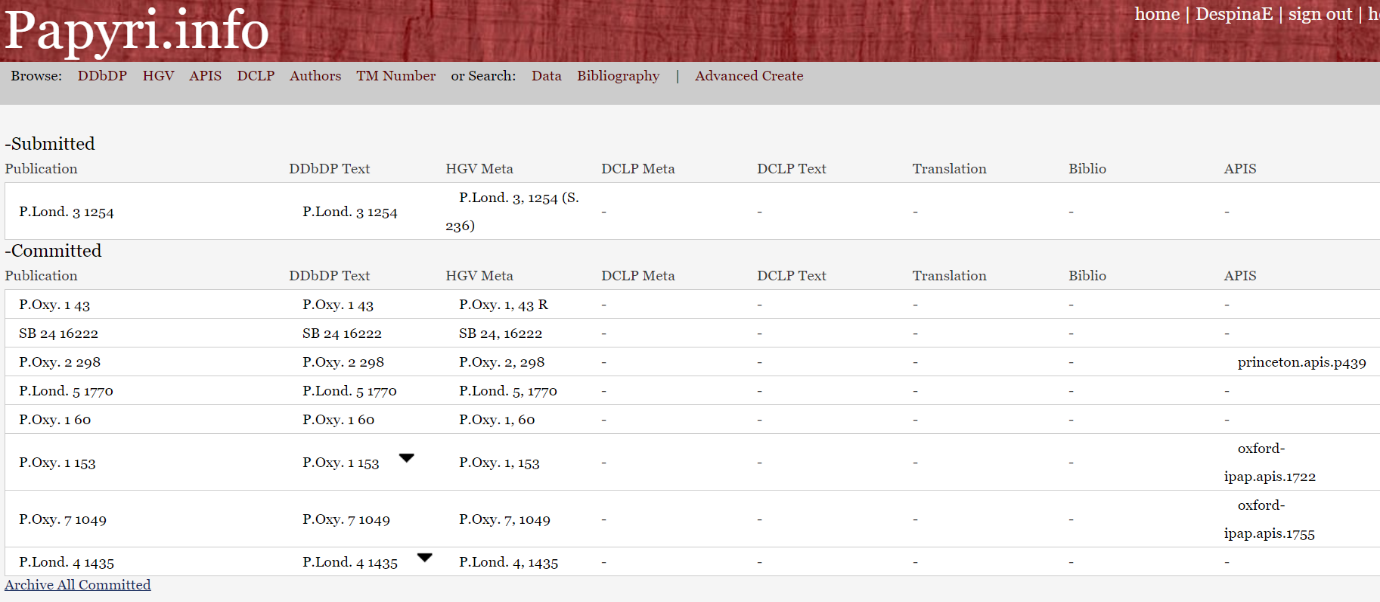

The options presented at the top of the editing window, as above, offer an author without full knowledge of Leiden+ the option to make amendments via a pop-up window (left). The accessibility of the interface is further emphasized by the ‘Find Error’ feature (same figure above), which identifies potential mistakes prior to the ‘Preview’ stage. This is a particularly useful tool for a Leiden+ beginner.  The Papyrological Editor also includes a guide to operating in Leiden+ as an alternative (right). The guidelines are detailed in separate sections accordingly. The practical nature of the examples found in the guidelines, highlighted below, facilitates editorial efficiency. The interface retains its overall clarity on the ‘Home’ page as well, which displays the status of the edits in progress, and the outcome of previous submissions:

The Papyrological Editor also includes a guide to operating in Leiden+ as an alternative (right). The guidelines are detailed in separate sections accordingly. The practical nature of the examples found in the guidelines, highlighted below, facilitates editorial efficiency. The interface retains its overall clarity on the ‘Home’ page as well, which displays the status of the edits in progress, and the outcome of previous submissions:

Lastly, one key strength of the PE lies in the appearance of Leiden+. With the exception that ‘Leiden+ must in some cases be more verbose than traditional Leiden, (…) due to the fact that Leiden+ must be able to be transformed into unambiguous, valid EpiDoc XML’ (Baumann 2013, p. 102), the syntax proved straightforwardly intuitive, because of how closely it resembles the Leiden conventions. The similarity further simplifies the encoding process.

Lastly, one key strength of the PE lies in the appearance of Leiden+. With the exception that ‘Leiden+ must in some cases be more verbose than traditional Leiden, (…) due to the fact that Leiden+ must be able to be transformed into unambiguous, valid EpiDoc XML’ (Baumann 2013, p. 102), the syntax proved straightforwardly intuitive, because of how closely it resembles the Leiden conventions. The similarity further simplifies the encoding process.

III.3 Overall Assessment

Babeu notes that ‘one strength of this model is that rejected proposals are not deleted forever, and are instead retained in the digital record, in case new data or better arguments appear to support them.’ (Babeu 2011, p.148). An example is shown in the figure below:

By keeping an accessible record of the edits on a papyrus, the PE interface strikes a balance, in that it stores useful information on a papyrus without overcrowding its interface. The point Damon makes about the despair of the philologist at the sight of different editions (Damon 2016, para. 39) is something that Papyri.info manages to avoid, as the PE’s flexibility lies in the possibility of averting or further exploring the prolixity of an apparatus criticus, according to the research needs of the scholar. In this way, the PE manages to ‘support the creation of ‘‘ideal’’ digital editions where the editor does not have to decide on a ‘‘best text’’ since all editorial decisions could be linked to their base data (e.g., manuscript images, diplomatic transcriptions)’ (Bodard and Garcés 2009, p.96).

Moreover, through its accessibility, the Papyrological Editor retains its constant potential to develop further. As such, the DDbDP is not ‘a fixed resource, finished at some date, unwavering and confident that it knows all; rather, it is a collection of conjectures, now easily capable of being revisited, revised, and improved.’ (Baumann 2013, p.105). This observation renders true through the PE instrument, which supports continuous editing, according to the state of the latest papyrological scholarship. In this way, its user friendliness allows the DDbDP collection to remain actual, and therefore relevant.

III.4 Greater Research Purposes

If used as a springboard, the model of the Papyrological Editor of Papyri.info may accommodate three possibilities. Firstly, its accessible interface could constitute a model for non-papyrological projects, to create textual databases for material in other languages. Secondly, its academically creditable and user-friendly approach, guaranteed by the assessment of an accredited editorial board, could also represent an example for other digital projects, both in the general sphere of Classics and outside. In this way, collections of printed editions of non-papyrological texts could acquire digital versions placed under constant review by authorised editors and thus become relevant databases for scholarly research, without the risk of being outdated. Finally, the content of the Papyri.info collections, constantly actualised through its Papyrological Editor, can be a springboard for other projects, through its Open Access license. An example is University of Helsinki’s PapyGreek project, mentioned by Vannini in her review of Papyri.info.

IV. Conclusion

As outlined in the previous segments, the accessibility of the PE interface of Papyri.info renders it an effective research instrument for specialised papyrologists and classical enthusiasts alike. Its user-friendliness is firstly reflected in the overall successful completion of the experiment, contradicting the original expectations of an author with no prior experience in digital papyrology. The PE interface model’s main lie in the straightforwardly useful board at the top of the editing window, the clear Leiden+ guidelines (accessible via the same window), and in particular the ‘Find Error’ feature, as well as the overall coherent design of the PE in relation to the PN, which facilitate ease of navigation. One other noted advantage was the straightforwardness of Leiden+, similar to the Leiden Conventions. Conversely, improvable features of the PE relate to its display: better time efficiency could be achieved if a parallel window with the original Leiden+ would appear at the time of editing; likewise, visibility of edits could be further emphasized in the ‘Preview’ section—particularly relevant for papyri with an extensive body and apparatus criticus.

The overall assessment of the interface renders it a balanced tool in its flexibility, transparency, and actuality. Thus, the purpose of the PE of Papyri.info is reached, as it represents the means through which ‘to give digital form now to the mature state of textual scholarship represented by print editions, while leaving open the possibility of adding the underlying image and transcription data when and if opportunities arise.’ (Damon 2016, para. 40). Moreover, ‘permanent transparency’ as ‘the guiding principle behind SoSOL’ is achieved via the edit-probing of a proficient editorial board, which may render the PE of Papyri.info a more competent and credible a research tool than other user-friendly instruments with informative purposes (e.g., Wikipedia). In this way, classicists (and others) without training in the sphere of Digital Humanities can contribute to the sphere of papyrology without being detrimental to the academic accuracy (and therefore, credibility) of this resource. The PE may also constitute a springboard for other research initiatives, through its model, approach, and content. Whether as an accessible digital tool in its own right or a springboard for other such initiatives, the Papyrological Editor of Papyri.info is an instrument which facilitates, through its accessible interface and model, continuous and up-to-date research, both in the sphere of Papyrology, as well as beyond it.

The Papyrological Editor also includes a

The Papyrological Editor also includes a  Lastly, one key strength of the PE lies in the appearance of Leiden+. With the exception that ‘Leiden+ must in some cases be more verbose than traditional Leiden, (…) due to the fact that Leiden+ must be able to be transformed into unambiguous, valid EpiDoc XML’ (

Lastly, one key strength of the PE lies in the appearance of Leiden+. With the exception that ‘Leiden+ must in some cases be more verbose than traditional Leiden, (…) due to the fact that Leiden+ must be able to be transformed into unambiguous, valid EpiDoc XML’ (

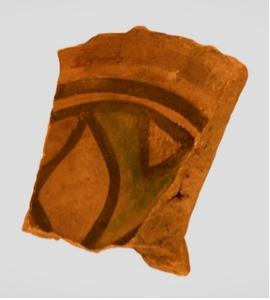

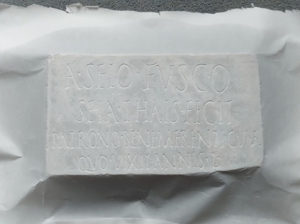

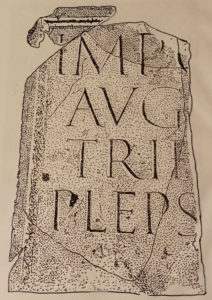

Before I arrived at the ICS, Gabriel provided me with some video tutorials and suggested that I familiarise myself with the theory and practice of photogrammetry, the process of combining multiple 2D images to create a 3D model using specialised software. The tutorials provided me with sufficient knowledge to photograph the objects myself, and to merge them using Agisoft Metashape and Autodesk MeshMixer. Over the two-week period, I was able to successfully digitise six items from the library’s collection, putting aside a couple more after several failed attempts at producing a complete model. These latter items were similarly imaged from inside a light tent (shown above right), but their uniformly black surfaces proved too reflective for the software to accurately identify and so the model was repeatedly rendered with gaps. Through trial and error, I learnt that more detail often correlated with greater accuracy in the final 3D model as the software was able to detect a higher number of overlapping points.

Before I arrived at the ICS, Gabriel provided me with some video tutorials and suggested that I familiarise myself with the theory and practice of photogrammetry, the process of combining multiple 2D images to create a 3D model using specialised software. The tutorials provided me with sufficient knowledge to photograph the objects myself, and to merge them using Agisoft Metashape and Autodesk MeshMixer. Over the two-week period, I was able to successfully digitise six items from the library’s collection, putting aside a couple more after several failed attempts at producing a complete model. These latter items were similarly imaged from inside a light tent (shown above right), but their uniformly black surfaces proved too reflective for the software to accurately identify and so the model was repeatedly rendered with gaps. Through trial and error, I learnt that more detail often correlated with greater accuracy in the final 3D model as the software was able to detect a higher number of overlapping points.

This seminar is organized by Gabriel Bodard and Rada Varga and co-hosted by the Digital Humanities Research Hub, University of London, UK, and Star-UBB Institute of Advanced Studies, University Babeș-Bolyai, Cluj Napoca, Romania, from autumn 2021–spring 2022. All sessions are online and free to attend, but booking is essential (see below).

This seminar is organized by Gabriel Bodard and Rada Varga and co-hosted by the Digital Humanities Research Hub, University of London, UK, and Star-UBB Institute of Advanced Studies, University Babeș-Bolyai, Cluj Napoca, Romania, from autumn 2021–spring 2022. All sessions are online and free to attend, but booking is essential (see below).

Julia Flanders & Charlotte Roueché, 2006 (2021)

Julia Flanders & Charlotte Roueché, 2006 (2021)