Introduction

Between April and May 2025, the University of Parma hosted the Erasmus+ funded Blended Intensive Programme (BIP) “Intensive ENCODE: Digital Competences in Ancient Writing Cultures.” This initiative is a spin-off of the ENCODE project (2020–2023), an international collaboration that aims to bridge the gap between traditional humanities education and the digital skills increasingly essential for the study of ancient written cultures.

Structured in two phases, the programme combined online learning (1 April–12 May) with an in-person week in Parma (18–24 May). It brought together around 70 Bachelor’s and Master’s students from across Europe, representing partner institutions in Germany (Cologne, Leipzig, Würzburg), Norway (Oslo), Italy (Bologna), Greece (Komotini), Spain (Madrid), Lithuania (Vilnius), and Bulgaria (Sofia).

What united this diverse group was a shared curiosity: how can digital tools reshape the way we explore the texts, scripts, and writing systems of antiquity?

In the blog post that follows, Elena Di Giorgio, Giulia Contesini, Alberto Negri, Violina Hristova, Stephanie Daneva, Nicoletta Nannini, Stephania Daviti, and Athena Mega, participants in the BIP, share their thoughts on some of the key themes that emerged from the guest lectures and collaborative activities.

Fig. 1: Students and teachers of the Erasmus+ Blended Intensive Programme (BIP) “Intensive ENCODE: Digital Competences in Ancient Writing Cultures”

Relationship with writing

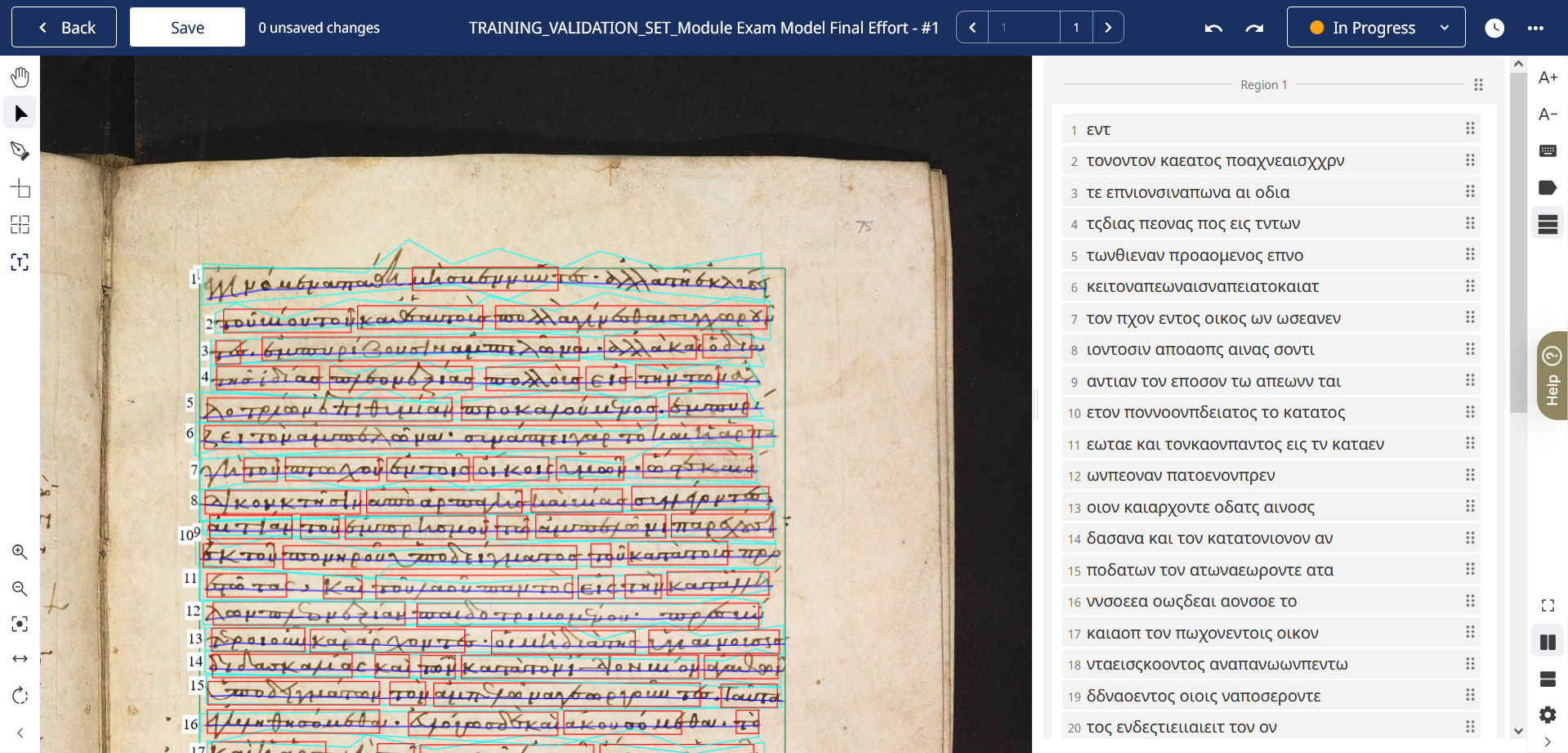

Nowadays, Artificial Intelligence is revealing itself as an essential tool for many tasks pertaining to any kind of field. When it comes to historical studies, AI might be trained for the purpose of automatic recognition of texts.

Pursuing such a goal, Isabelle Marthot-Santaniello applied Deep Learning-based methodologies to papyri. In the D-scribes project she worked towards identifying all the scribes responsible for the notarial documents of the archive of Dioscoros of Aphrodito. To do so, first and foremost she established a ground truth, consisting of a preliminary dataset of images representing the known handwriting of each scribe. These samples were narrowed down to καὶ-s along with some single letters (ε, κ, μ, ω), which display marked palaeographic features and show few, if any, variations in their ductus. With these specimina a confusion matrix was produced, a table that is used to define the performance of a classification algorithm. Currently, this modus operandi works well with inter-writer discrimination, but struggles with intra-writer variations. The same principle was applied to dating papyri.

The idea of automatic letter recognition was applied also in Egyptology. The Demotic Palaeographical Database Project led by Franziska Naether allows users to draw Demotic signs, so that the AI tool can attempt to identify them, even suggesting possible matches. In terms of Unicode, hieroglyphs are not yet fully represented; moreover thousands of signs, such as those found in Demotic and Hieratic scripts, still need to be accounted for. A similar challenge exists in Mycenaean studies. As a result, scholars in both fields continue to rely primarily on transliterations.

Moreover, Jérôme Mairat illustrated how helpful AI proved itelf in modeling digital editions in Numismatics (RPC online). He used AI to generate interpretations, and even translations, of Roman coin legendae, brief but dense inscriptions containing several abbreviations. Remarkably, a fine-tuned version of OpenAI’s GPT-4o-mini proved capable of recognising both Greek and Latin characters, delivering promising results with an estimated 95% accuracy rate. Of course, occasional errors and the well-known phenomenon of AI “hallucinations” still occurred. To refine the output, he employed APIs to automate the creation of both a textual edition (following Leiden conventions) and a basic EpiDoc XML file. For these more mechanical tasks, he favours using a dedicated web app, which is both more cost-effective and more reliable, unlike OpenAI, it performs the job without error.

Non-textual aspects of the writing support

The material characteristics of ancient artifacts bearing text on their surfaces must be duly taken into consideration within historical disciplines concerned with the study and interpretation of the text itself.

Papyrology, for example, is a discipline marked by a high degree of fragmentation of writing supports, and for this reason it requires constant comparison between artifacts with similar content, in order to reconstruct missing text in any existing gaps. A similar approach, though less pronounced, also applies to epigraphy in the assessment of missing or hard-to-read portions of stone.

These specific aspects of studying ancient sources are by no means marginal in DH; on the contrary, the digitization of such sources calls for methodological reflection. A useful point of reference is the Digital Marmor Parium project, led by Monica Berti. In working with this epigraphic document, particular attention is paid to the editorial layer during the encoding process, especially in areas where the text is fragmentary. When reconstructing missing portions, it is crucial not only to propose plausible readings but also to clearly indicate the editorial choices made and the degree of certainty involved.

Among the non-textual data of the writing support, iconography also occupies a place of common interest. A relevant example of the attention dedicated to this field of studies is the Orasis project, one of the digital epigraphy projects developed in Bulgaria which were presented by Elina Boeva. Orasis is a digital platform for visualizing and presenting inscriptions from monuments of Christian art from the Byzantine and post-Byzantine period on the territory of Bulgaria and other Balkan countries. In this useful resource, it is possible to find a detailed description of the location of the image in the context of the iconographic program of the church.

Two more examples of digital endeavors in the humanities are worthy of mention. The first is the database MetrICa (Metrical Inscriptions of Campania) carried on by Pietro Liuzzo. MetrICa aims at investigating the relationship between the text and its material supports, graphic rendering, paleography, and the original archaeological context, when it can be reconstructed, emphasizing the importance of reuse of open data and collaboration.

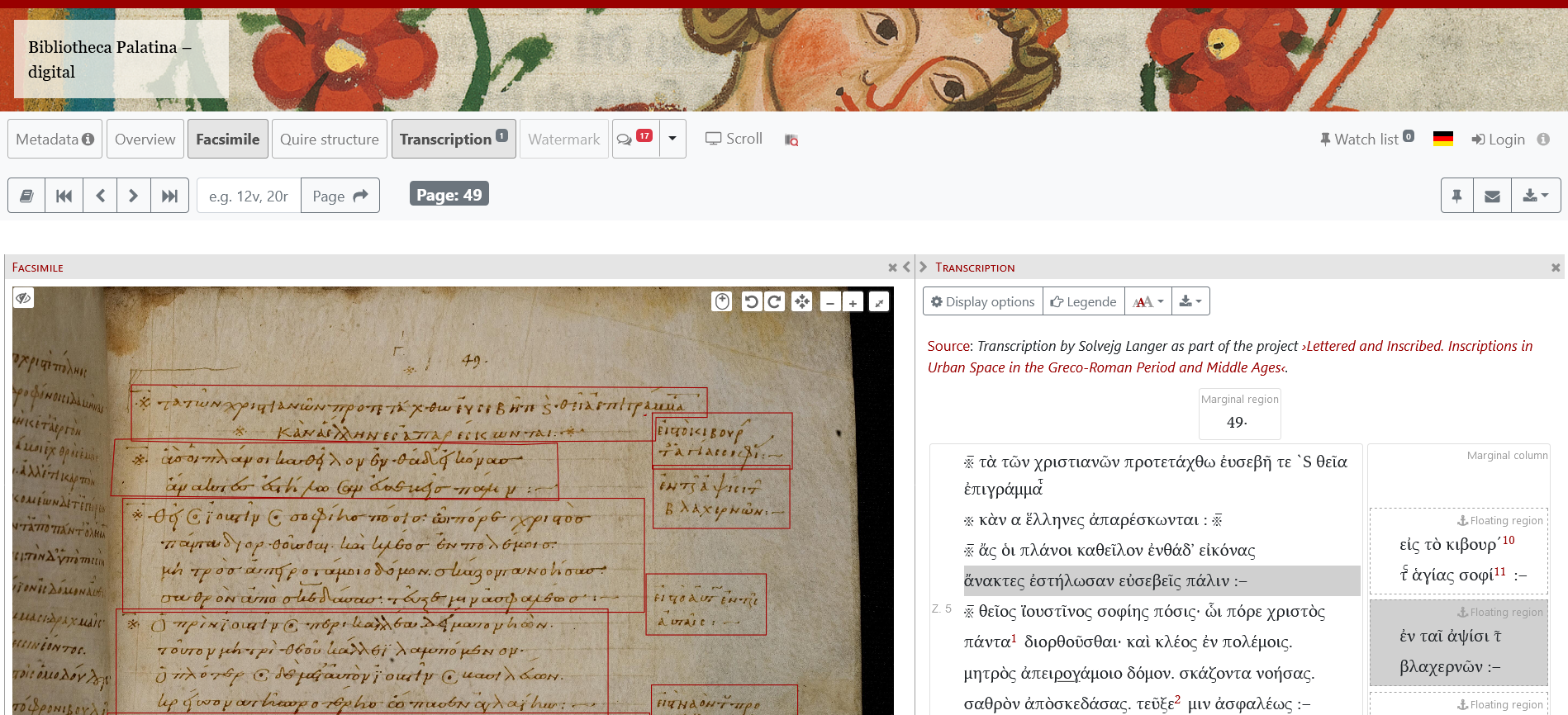

Digital Scholarly Editions

In recent years, numerous projects in the field of Digital Humanities have emerged and evolved, each dedicated to different types of artefacts from antiquity. The diversity of research objects, project goals, and established scholarly traditions requires a range of methodological approaches, sharing a common objective: to produce high-quality, scholarly, and accessible digital publications, following the FAIR principles.

The already mentioned Digital Marmor Parium project, for example, uses annotation and named entity extraction to build a database designed not only for specialists in linguistics and literature, but also as a resource that can be integrated into broader research initiatives. The process of extracting this type of data from epigraphic monuments and papyri presents several challenges: not all resources and authority lists are openly accessible for instance, Trismegistos, and others suffer from structural issues.

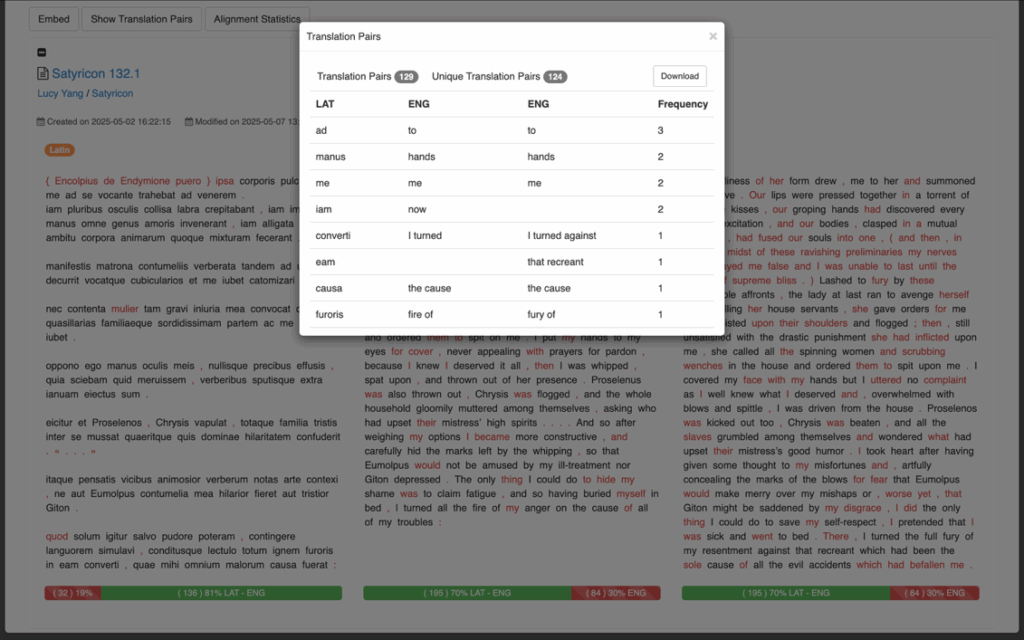

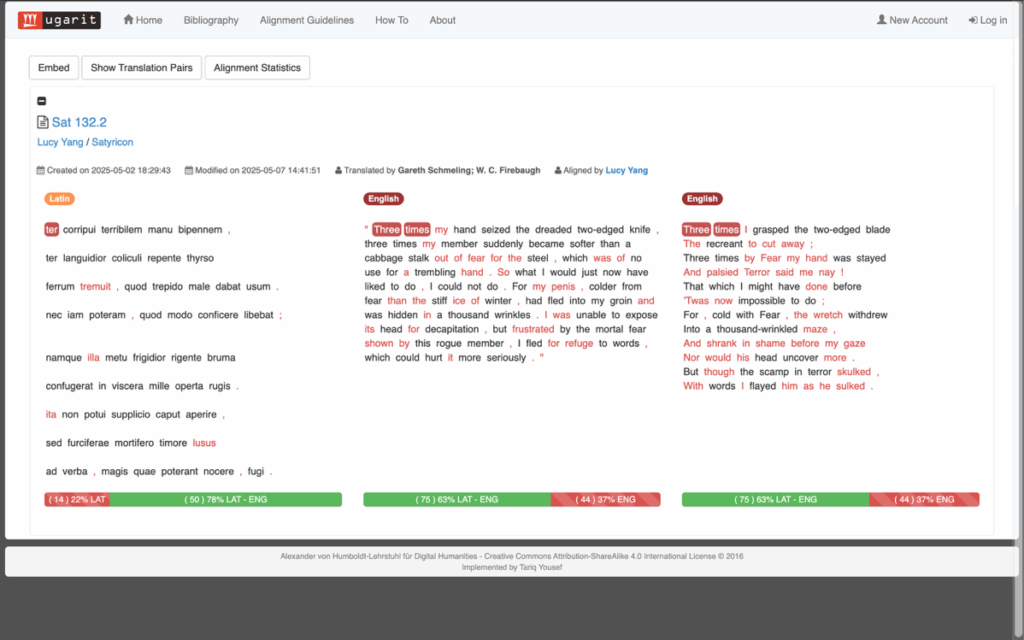

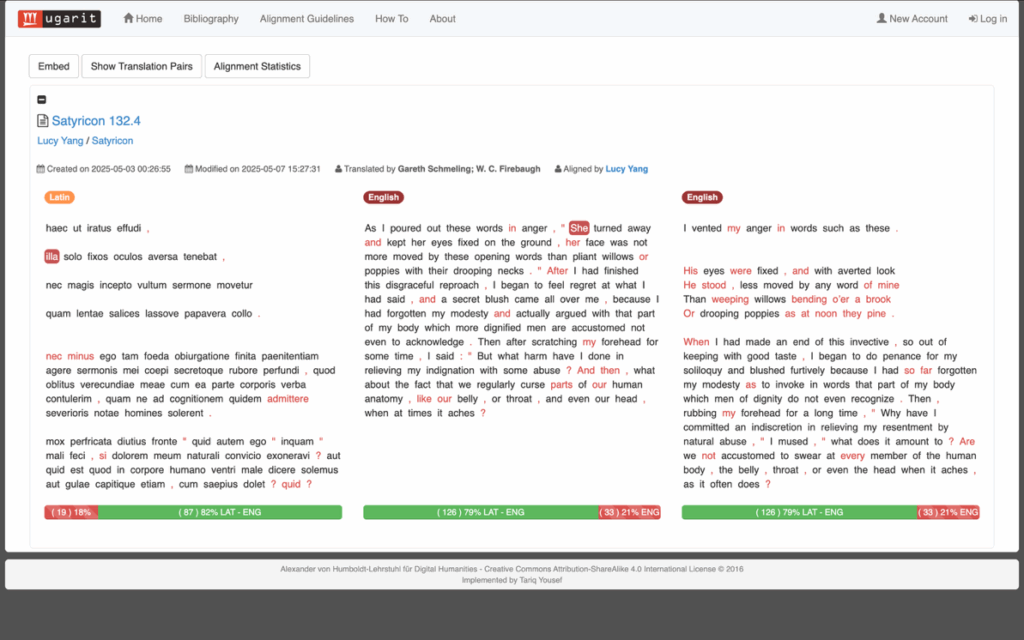

One particularly ambitious project is The Digital Rosetta Stone by Franziska Naether, Monica Berti, and their team, which combines 3D models of the monument, high-resolution imagery, visual alignment of the hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Ancient Greek texts, and tools such as Treebanking, semantic annotation and text alignment (Ugarit).

Similarly, the Damos project by Federico Aurora, a database of Mycenaean inscriptions, demands a tailored approach to text encoding due to the unique features of Mycenaean Greek. When encoding these inscriptions using EpiDoc, numerous difficulties and inconsistencies arise in comparison to encoding inscriptions in Classical Greek or Latin. A notable distinction lies in the requirement to annotate each word explicitly in Mycenaean texts, since some are represented by logograms a necessity not present when working with texts in Classical Greek or Latin.

In Bulgaria, key examples include the Tituli (Latin inscriptions), Telamon (Greek inscriptions), and Orasis (Byzantine texts found in churches), presented by Elina Boeva. The projects focus on producing digital publication of the inscriptions, using an EpiDoc template, tailored specifically for the needs of each project.

The model of digital publishing increases accessibility, allowing broader public and academic engagement without requiring physical access or paid subscriptions. However, it also comes with challenges, including the ongoing need for institutional funding to support hosting, maintenance, and database updates.

Content and meaning

Using digital tools for the study of Greek and Latin Epigraphy and Papyrology aims to offer inspiring content, fostering awareness of the importance of digital competencies, training in the field of research, as well as study of ancient writing cultures. The analysis brings out a range of linguistic and semantic aspects that were previously difficult or time-consuming to explore and promotes the digital transformation of cultural heritage by bridging the disciplinary gaps.

Digital technologies have significantly advanced paleography and script recognition. Computer vision techniques facilitate the identification of characters in damaged manuscripts, while machine learning models enable precise dating of handwriting styles such as uncial and cursive scripts. Morphological analysis benefits from automatic lemmatization and tagging, particularly in inflected languages like Ancient Greek and Latin. Additionally, digital syntax parsing improves reconstruction of incomplete structures and detection of formulaic expressions in legal and religious texts. These methods also support the study of linguistic variation, including dialectal differences, orthographic shifts, and code-switching phenomena.

Moreover, digital tools play a crucial role in exploring semantic aspects of ancient texts. Named Entity Recognition (NER) automatically identifies personal names, places and institutions, facilitating the construction of prosopographical databases by linking individuals across documents. Topic modeling and thematic clustering enable the detection of recurring themes, such as taxation, marriage, or military service, across large corpora, supporting semantic classification and contextual analysis. Tools for intertextual and citation analysis uncover textual reuse, quotations, and allusions to earlier literary, legal, or religious sources, shedding light on intellectual networks and the transmission of knowledge over time.

Digital projects analyzing ancient texts increasingly employ computational methods to investigate linguistic and semantic features. Named Entity Recognition (NER), used by Trismegistos, Papyri.info and the Digital Marmor Parium project identifies and standardizes personal and place names, aiding prosopographical and geospatial analysis. Morphosyntactic annotation, as in the Perseus Digital Library, addresses the complexity of inflected languages like Ancient Greek and Latin. Semantic disambiguation techniques, such as word embeddings and topic modeling (e.g., Tesserae), resolve lexical ambiguity. Thematic clustering, seen in the Digital Corpus of Literary Papyri, supports text classification. Projects like Pelagios emphasize intertextuality and citation networks. Multilingual corpora (e.g., Greek-Coptic) and infrastructures like CLARIN, DARIAH-EU, and ENCODE further enhance scholarly research.

Linked Open Data and Semantic Web technologies are crucial for digital analysis of ancient texts. EpiDoc, based on TEI-XML, standardizes encoding of inscriptions and papyri with rich metadata. Projects like Trismegistos use RDF to link entities via ontologies such as Pleiades and SNAP:DRGN, promoting integration. The Pelagios Network connects texts to geographic data for spatial analysis. Tools like Papyri.info Editor and Recogito support collaborative annotation, while databases such as EDH and EAGLE offer structured, API-accessible resources enhancing interoperability and epigraphic research.

Variety of languages, chronology, and civilizations

Studies of ancient civilizations must contend with a history made up of places, chronologies, and, above all, extremely diverse languages. When these fields of study intersect and engage with the domain of digital humanities, the result is the need for digital tools with specific features: they need to be capable of conveying the diversity of content, depending on the contexts under examination, in a way that is as simple as possible for developers to use and as accessible as possible for the audiences who rely on them.

One of the most significant aspects in the encoding of ancient texts lies not only in the goal of making the texts increasingly accessible, but also in connecting features that may be shared across different languages and civilizations, as through the analysis and study of linguistic aspects.

For instance, it is precisely from this perspective that was created the WordNet project, a large lexical database or “electronic dictionary”, developed at Princeton University for Modern English. The aim of WordNet is to collect and interlink not just words based on their meanings, but specific senses of words. WordNet labels the semantic relations among words and provides information about two fundamental properties of the lexicon: synonymy and polysemy. In the study of ancient languages, it proves especially useful to link WordNets with other textual and lexical resources and it reveals connections between the semantics of lexical items and their syntactic context. Especially in philology, this connection may help researchers filling gaps in the written records, as entire sets of near-synonymic and semantically related words will be easily made available.

Furthermore, the project faces a pivotal challenge: whether to adopt English synsets as a foundational structure an approach that risks significant inaccuracies or to construct an entirely new synset framework, which would require extensive linguistic and technical effort. Additionally, ancient languages contain conceptual distinctions that are not lexicalized in English, e.g. avunculus and patruus refer to maternal and paternal uncles – distinctions not explicitly encoded in English.

Call for Presentations

Call for Presentations