written by Valquirya Borba, graduate student, University of Oxford

In March 2021, during the coronavirus pandemic, I signed up to take part in an introductory digital humanities course, convened by Dr. Rada Varga (UBB), and held online. During this course, I learnt how to build and visualise networks using Gephi, an open-source network analysis and visualisation software. Over this same period, I was also finishing a research masters degree in philosophy, thinking about two texts in particular, Hesiod’s Theogony and the Babylonian Enuma Eliš. These are two cosmogonical texts, which tell a broadly similar story about how the patron god of their respective places of origin (Greece and Babylonia) came to be kings of the gods. The similarities between these two texts have been studied since the mid-20th century. For my final project on the digital humanities course, I decided to build databases of the characters and their relationships, and plot the networks of these two texts, in order to explore a different approach to this comparison.

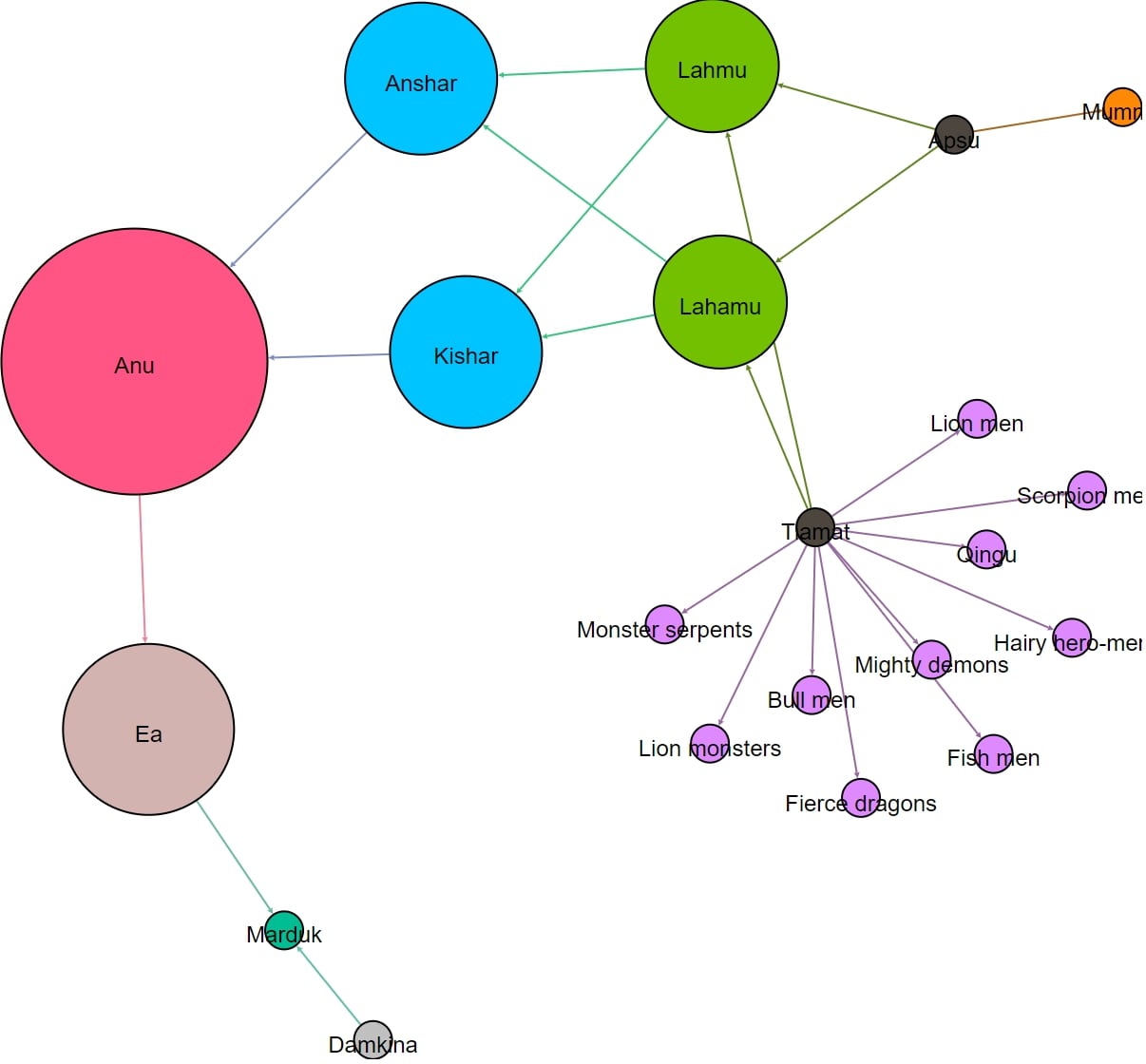

Both the Theogony and the Enuma Eliš detail a genealogy of their gods. In any genealogy, two kinds of relationships are particularly important: parent-child relationships, and the relationships between sexual partners. When we start to think about this, one major difference between the two texts becomes immediately obvious: the Enuma Eliš network is much smaller than the Theogony network. The former has 21 characters, whereas the Theogony has 144. Why these texts differ in this way is an interesting question. We might think that this reveals different authorial intentions. Hesiod’s Theogony is clearly meant to be an exhaustive treatment of the Greek pantheon, whereas the Enuma Eliš is clearly focused on one particular story; Marduk’s ascent to the throne.

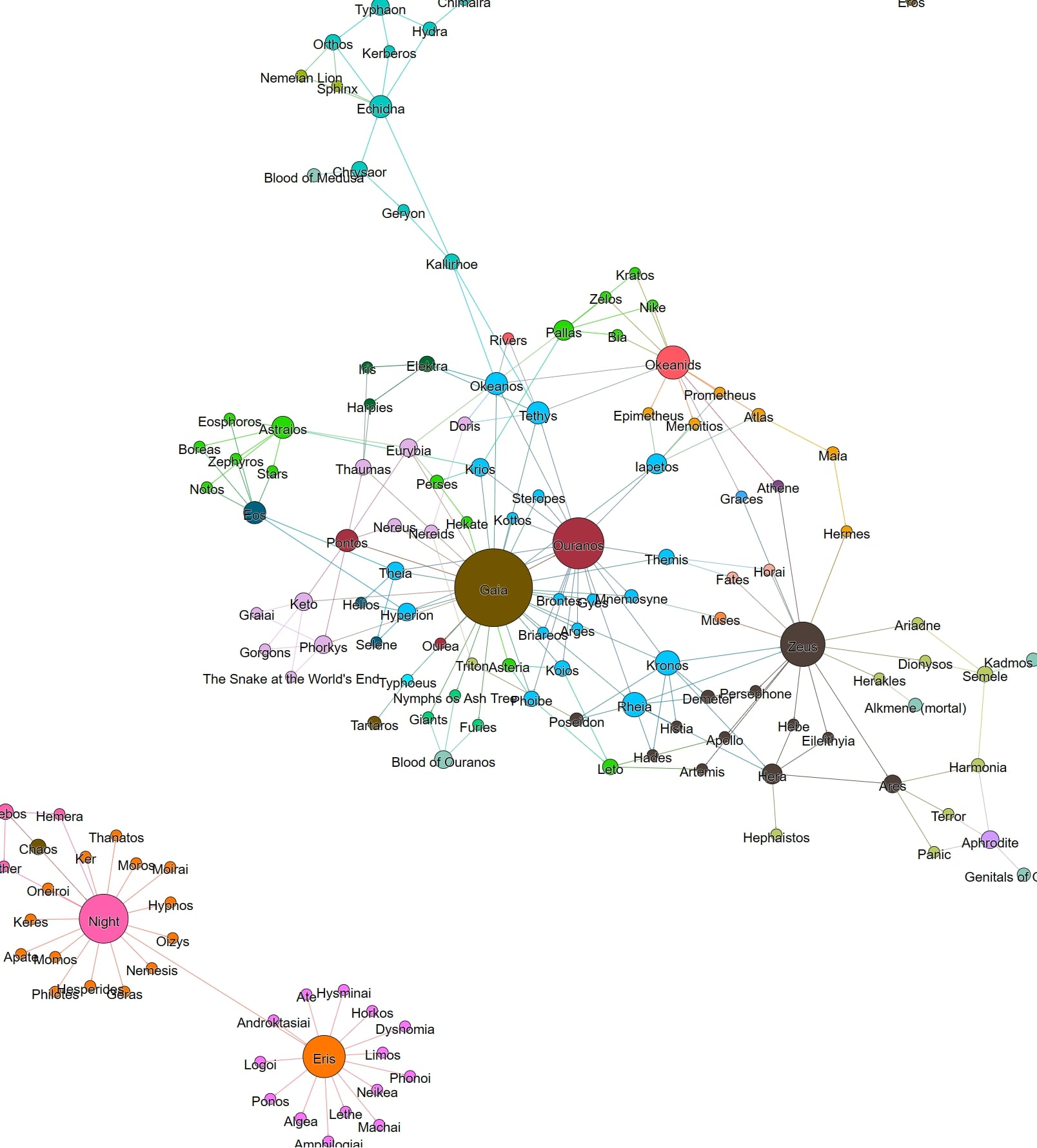

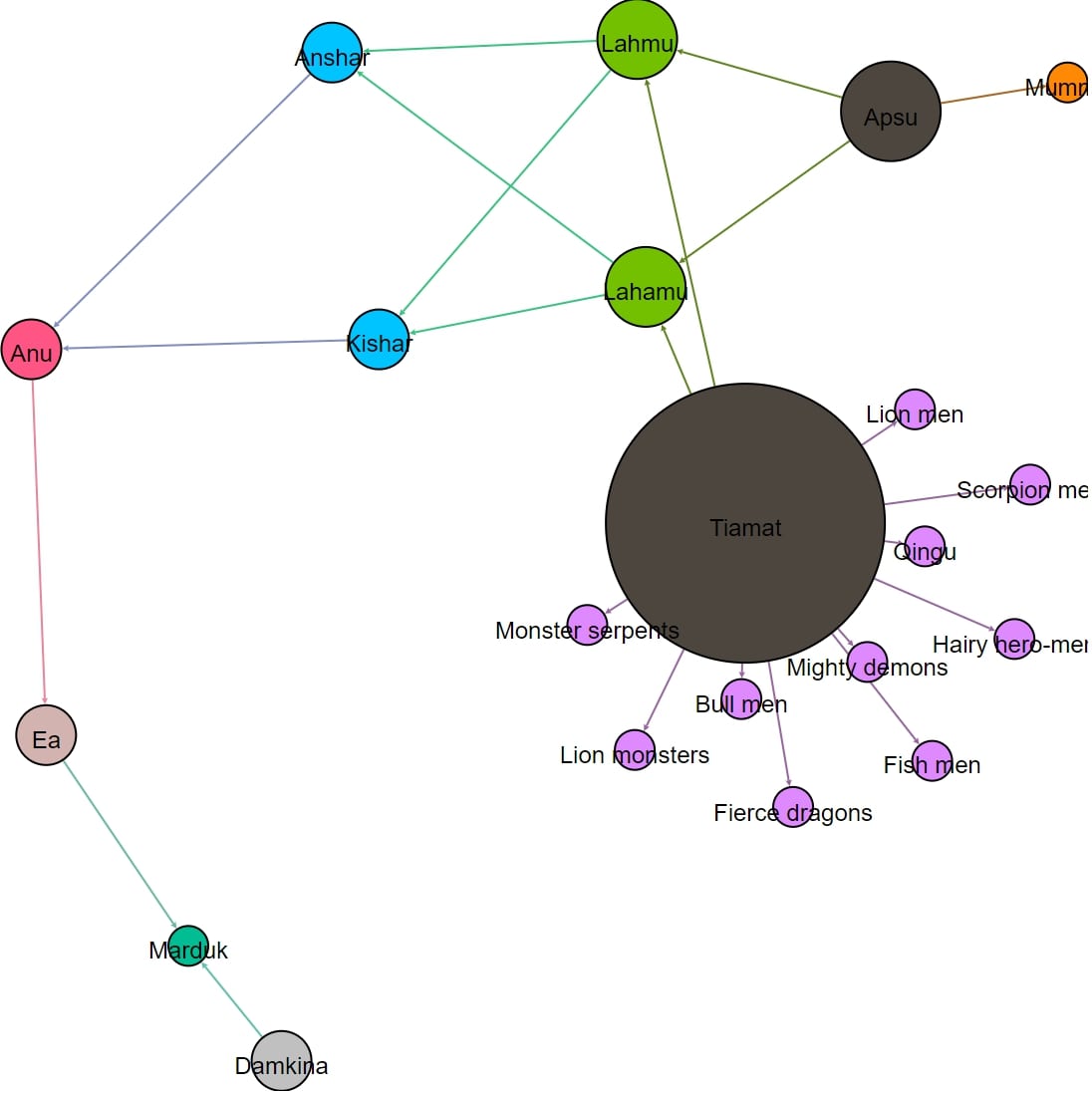

The network in Fig. 1 (above) highlights the characters in the Theogony that have the most children. In this respect, Gaia, is the most important character in the text, without whom the network of the Theogony would be vastly diminished. The second most important character is her son and partner Ouranos, the first god-king. (I leave for the reader to ponder the significance of the disconnection of Night and Eris from the main network.) Compare here Fig. 2, which highlights the fact that Tiamat, who plays a role that is, in some ways, analogous to Gaia in the Theogony, is also the largest node in her network, seeing as she has the most children. But this is not because Tiamat is as important to the story as Gaia, for most of Tiamat’s children are monsters, who feature only in the battle between Tiamat and Marduk, and whilst it is true that Marduk must win this battle in order to be worthy of being crowned king of the gods, these monster characters are not important as individuals, and contribute next to nothing to the plot. So whilst Tiamat is an important character, in the sense that she is the original mother of the gods, she is not any more important than her partner, the original father of the gods, Apsu. This is a crucial piece of context that helps us to understand that, whilst the networks of the Theogony and the Enuma Eliš might look similar in some respects, there are important differences underlying these apparent similarities.

Another striking aspect of the network in Fig. 2 (above) is that Marduk is as small a node as Tiamat’s monsters (and Apsu’s vizier, Mummu). This is striking because this text is, after all, an exaltation of Marduk, king of the gods, god of Babylonia, creator of the world, but it tells us nothing about his children. The Theogony, on the other hand, details Zeus’ many wives and children, which one might reasonably think is a testament to his power and influence. This highlights a further difference between our two texts: sexual reproduction, and the having of children, is not as significant to the Enuma Eliš as it is to the Theogony. We might conjecture that this is because the whole cosmos of the Theogony develops organically via sexual reproduction, whereas the cosmos of the Enuma Eliš is a product of creation and design. In the Theogony, for instance, the rivers are deities, born from the sexual union of other gods, but in the Enuma Eliš, these are designed and created by Marduk after he defeats Tiamat and her monsters in battle. This hints at a significant difference between our two protagonists: Zeus’ power comes from his centrality in the network, whereas Marduk’s power comes not from his function in the network, but from his role as creator of the world.

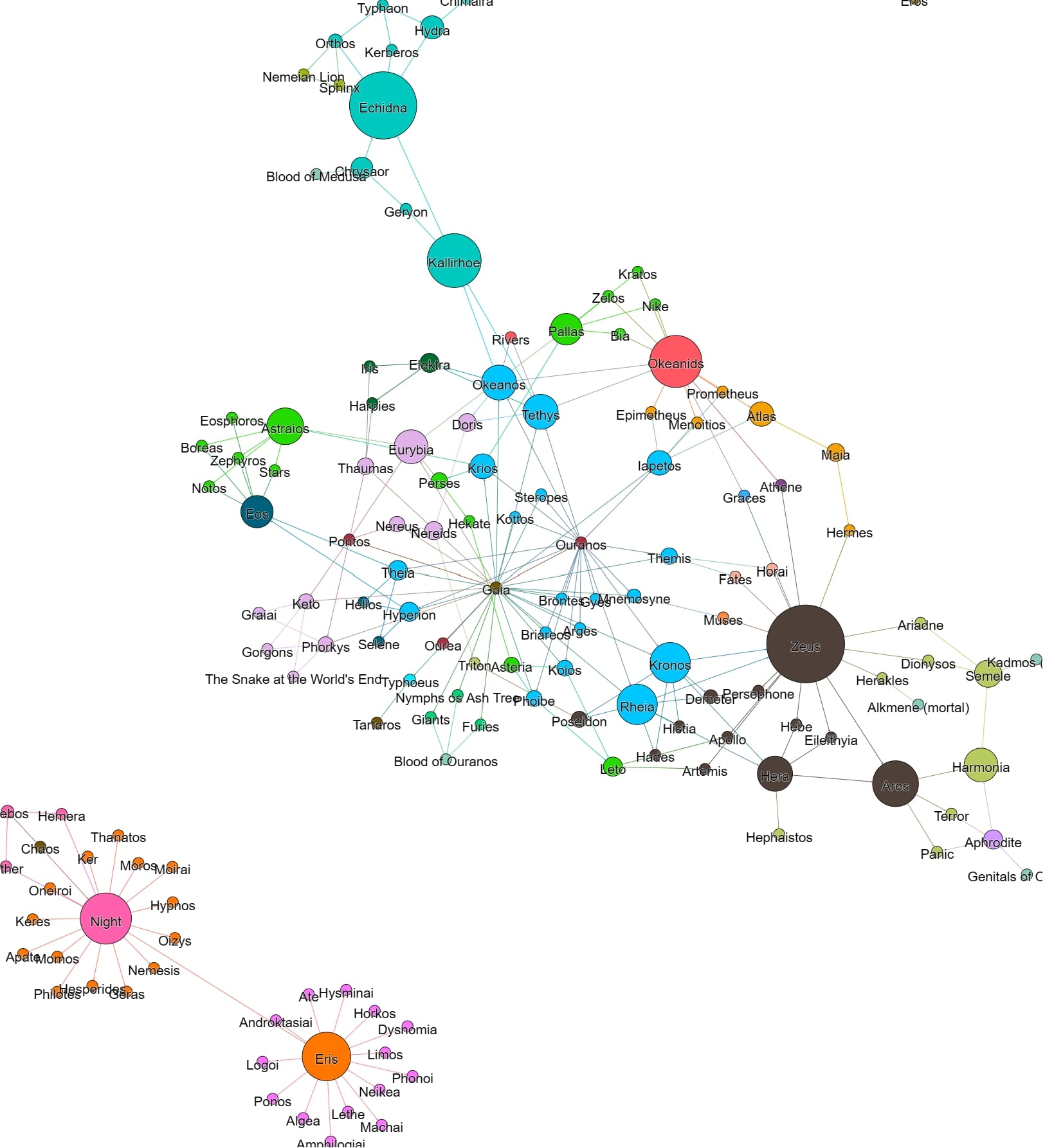

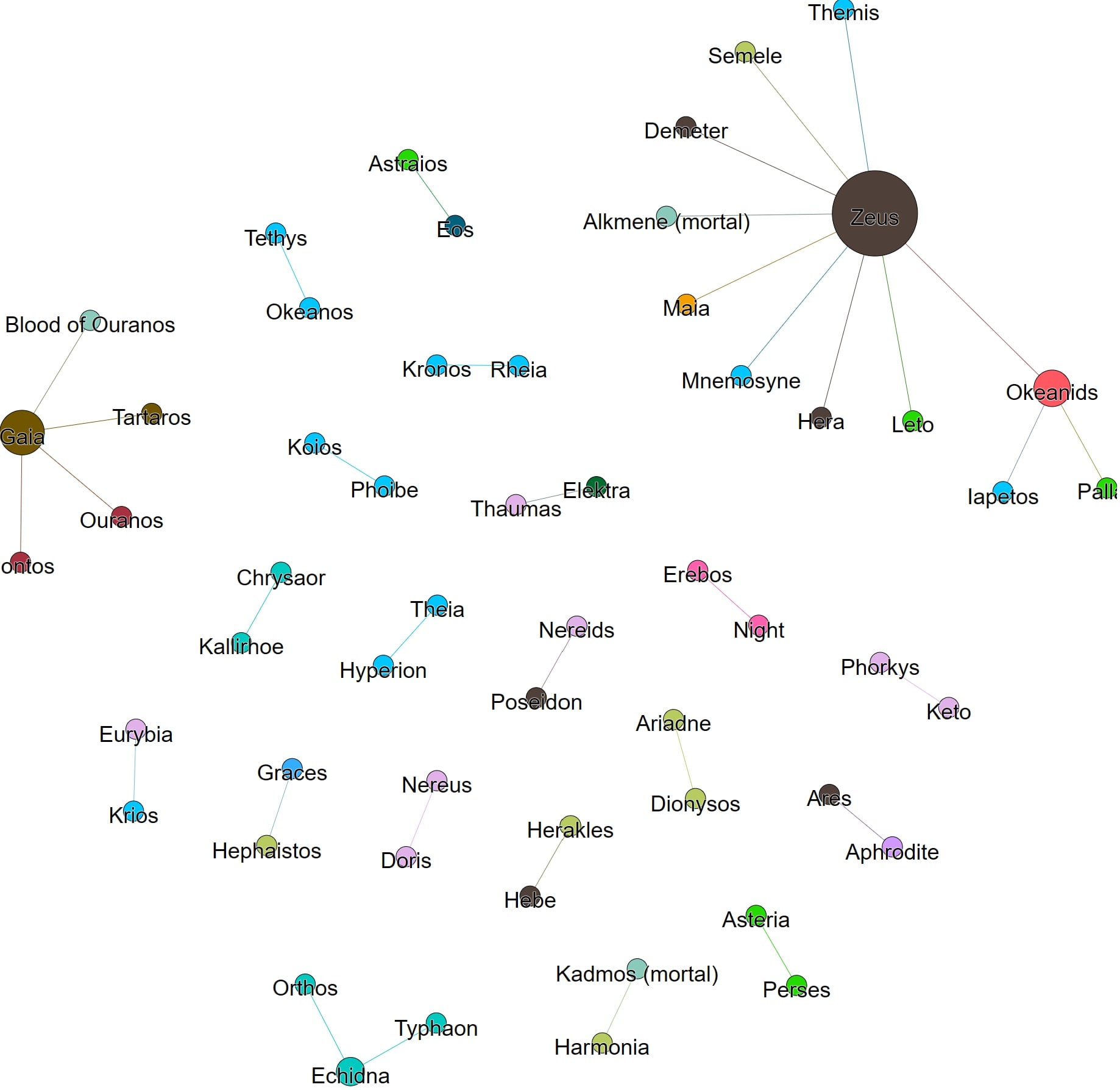

This is even clearer when we look at Figs. 3, 4 and 5. The network in Fig. 3 (above) shows Zeus is the most central member of the network of the Theogony; again, this is where his power and influence lies.

The network in Fig. 4 (above) shows that Zeus has, by far, the most number of romantic/sexual relationships in the Theogony; again, this underpins his power and influence.

On the other hand, Marduk is the smallest node in the network in Fig. 5 (above), as he lies at the very edge of the network of the Enuma Eliš, connecting no nodes. It is also interesting that Anu is the biggest node in this network. Anu is the father of Ea, the second king of the gods in this narrative, suggesting that his power and influence comes from his centrality, like Zeus. Further to this, we need not even plot a network of the romantic/sexual relationships of the Enuma Eliš to see that Marduk would be entirely disconnected, for he has no romantic/sexual relationships narrated in that text. This underlines an important difference between these two, otherwise similar texts: Zeus’ power and influence can easily be explained by his centrality and his connections to other members of the network of the Theogony, but Marduk’s power and influence is more elusive, whilst he is the protagonist of the Enuma Eliš, king of the gods, he is a largely insignificant member of the network when it comes to parent-child relationships, and romantic/sexual relationships. Whilst Zeus and Marduk play similar narrative roles in their respective texts, they play very different roles in their respective social networks. I will, again, leave the reader to ponder what this difference might entail.

This short post gives a flavour of the kinds of insights I was able to achieve through a comparative network analysis of these two ancient texts during the UBB digital humanities course. That a novice digital humanist like me can already learn so much about these texts from a comparative network analysis is reason enough to pursue this work further; there is much else, I suspect, that we might discover about these two texts with further statistical calculations and visualisations.

Was this study published in a indexed journal? If it was, please, share with us.

No, it was not so far. You can reference it from here, if you want to.

Yes, to clarify, the Stoa Review is a journal (albeit light-touch peer reviewed), with an ISSN (2635-0076) and indexed by the British Library. Articles on this site are citable as such, if you need to. This piece can be cited as:

Valquirya Borba. 2021. “Divine networks: a novice’s comparison of Hesiod’s Theogony and the Babylonian Enuma Eliš.” Stoa Review 2021-06-24. Available: https://blog.stoa.org/archives/4064