written by Annamária – I. Pázsint, scientific researcher, Babeș-Bolyai University

Context

As part of an individual research project funded by the European Association for Digital Humanities, the population of Augusta Traiana has been studied based on the epigraphic sources, in order to provide glimpses on it and on the networks that existed inside the society. While the results of the research have been synthesized in an article sent for publication (Romans 1 by 1. Augusta Traiana et territorium), the goal of this blog entry is to address some of the discussed aspects.

Sources

The Roman city of Augusta Traiana was founded by the emperor Trajan in the nearby the Thracian settlement Beroe, and over the centuries it became the second-largest center of the province Thrace, after Philippopolis. From its earliest epigraphic attestation and up to the 3rd century AD, there are 276 inscriptions from the city that provide information on its population (mostly from the 2nd and 3rd century AD), be it on persons who were temporarily or only permanently located there. Certainly, as in the case of all such initiatives based on epigraphic sources, the evidence does not record the population in its entirety, only a fraction of it. In spite of this, such studies are relevant because they show specific epigraphic habits and point to those persons who, for some reason, are mentioned on monuments, be they dedicatees or dedicators, and in the end, it points to the existing evidence. In order to make the prosopographical evidence available for anyone interested in it, specialist or not, each person epigraphically attested has been recorded in the prosopographical database Romans 1 by 1. The database is a work-in-progress initiative and it includes all of the existing prosopographical evidence on the persons epigraphically attested in the Roman provinces of Moesia Inferior, Moesia Superior, Dacia and Pannonia Superior, as well as the evidence on specific cities from other provinces.

Exceptions

Given the sources used, we applied some exceptions to the corpus we gathered; as such we have excluded the emperors or the provincial governors that some inscriptions mention at Augusta Traiana, for the simple reason that they were not inhabitants of the city. Based on the same criterion, excluded from the sample were also the personal names mentioned on amphoras, as they do not necessarily attest local craftsmanship. Unfortunately, due to the fact that some inscriptions were fragmentary, we could not “extract” the personal names mentioned in them – this is mostly the case of votive monuments.

Sample

For the period under our focus (up to the 3rd century AD), from the inscriptions result 525 “active”/“primary” persons. By “active”/“primary” I refer to those persons who were the subjects of inscriptions and by “secondary” I refer to the father of the “primary” person who is attested through the patronymic. When taking into account also the “secondary” persons, the number of persons attested at Augusta Traiana and its territory increases to 795. However, due to the fact that in this case many inscriptions provide very few information on the identity of persons and due to the increased attestation of identical personal names and patronymics, a drawback of the sample is detected; more precisely, it is very likely that some patronymics refer to the same person, and consequently some persons might have been recorded twice (fathers), while some relations (those between brothers) might not have been identified.

The profile of the population was reconstructed based on several markers, such as gender, personal name, age, origin, occupation, social and juridical status etc. Out of these we briefly address the gender distribution, as well as those markers that are more rarely mentioned, namely origin and occupation. The gender distribution is not surprising at all, being overall comparable to the situation reflected by the epigraphic sources in any ancient city, respectively attested is mostly the male population, while the female population is highly underrepresented (at Augusta Traiana it represents under 5% of the population), and here most women are part of the elite. Besides the local population, there were also persons who relocated at Augusta Traiana from other cities, their origin being sometimes explicitly mentioned, while at times it can be deduced from the onomastic of the persons, or other indirect evidence, such as the worshipped divinities. As such, the inscriptions mention persons from Nikaia (Δημήτριος son of Φωτογένης), Nikomedia (Οὔλπιος ῾Ιερώνυμος), but also from Perinthos (Στατίλιος Μάξιμος), Dacia (Αὐρήλιος Πρῖμος Ἄστεος ὁ καὶ Ἰούλιος), Pannonia (Μουκιανός; Κλαύδιος Φρόντων); additionally, some persons identified themselves as being Ἕλληνες (Νάρκισσος son of Ζήνων and Λολλιανός son of Ἀουῖτος), or Σύρος (Αὐρήλιος Σαβεῖνος son of Θειόφιλος). Occupation is an important identity marker of individuals and at Augusta Traiana mentioned are two gladiators ([—]ος ὁ καὶ Λεύκασπις; ignotus); three physicians: a ἰητρός (Ἀλέξανδρος son of Διλάης); a medicus of the cohors II Lucensium (Auluzenus); and a medicus (Δημοσθένης); a γραμματεύς (Αὐρήλιος Δημοσθένης son of Δημοσθένης); a κανδιδάρις – a baker of white bread (Ἡρακλιανός); a playwright (Νεικίας; father of Ηρωδιανός); an οἰνέμπορος {τῆς Δακίας} (Αὐρήλιος Σαβεῖνος son of Θειόφιλος); a κουκουλάρις – a manufacturer of hats (Φλάβις); an οἰκονόμος (Σειγηρός) and two actuari (Μᾶρκος Οὔλπιος Ἀρχέλαος and Ἰουλιανός). While based on it we cannot reconstruct with precision the occupational landscape of the city, these examples point to a certain variety and specialisation.

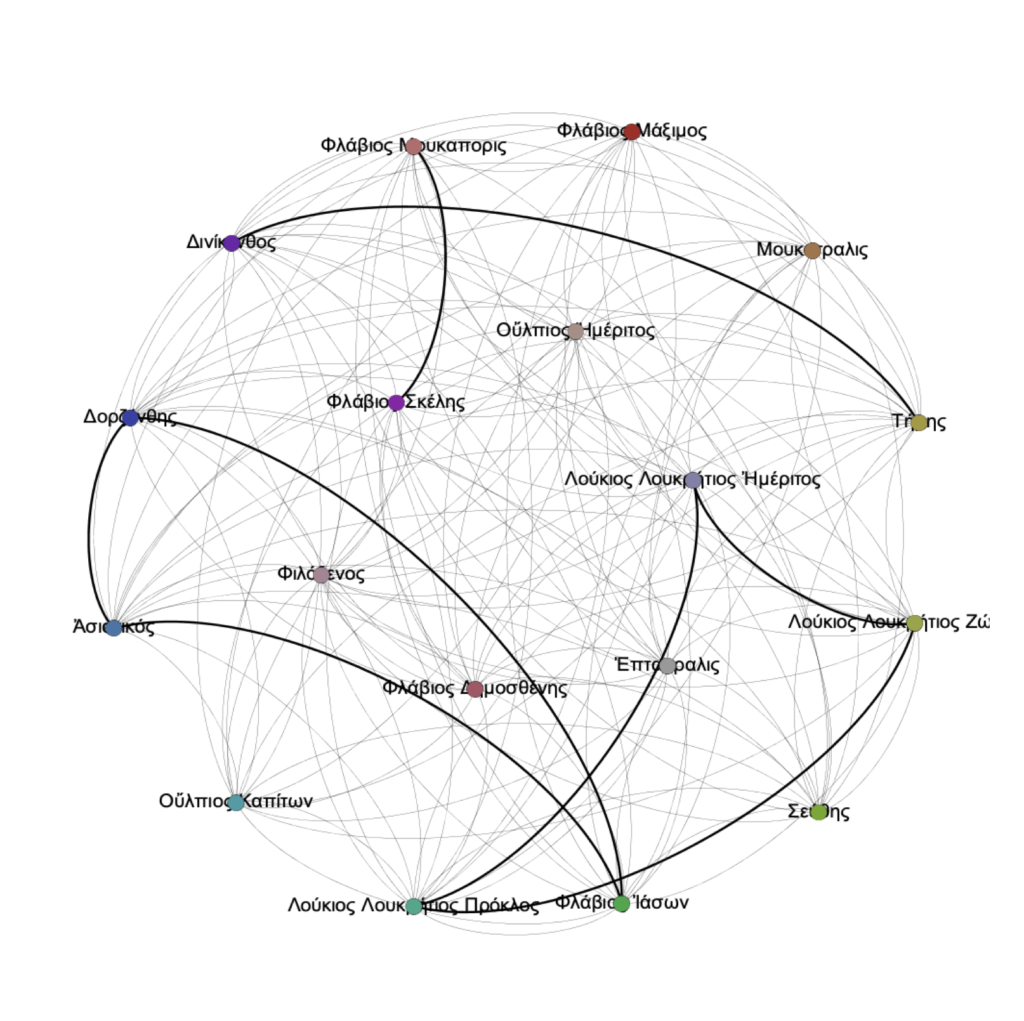

Fig. 1. The network of Εργισσηνοι

When discussing the population, the networks created inside society are an essential component of the global picture. The networks reflected by the inscriptions at Augusta Traiana are first of all familial, pertaining to the nuclear family, and only rarely to the extended family. Besides familial networks, attested are (with some missing links) also the religious, occupational, convivial and geographical networks. Certainly, based on indirect evidence we can imply wider networks for some categories of the population, such as the elite members, as is the case, for example of [Μᾶρκος] Αὐρήλιος Φρόντων son of Διοφάνης who was a was an athletic winner (Olympia and Haleia), as well as a Θρακάρχης and Εὐρωπάρχης. An example of a geographical network at Augusta Traiana is that of the Εργισσηνοι (IGB III.2, 1593), who dedicated a monument to Apollo Σικερηνος and the Nymphs. 18 persons are mentioned by the inscription under this name, the denomination pointing probably to the name of the village from which they came. Among them, based on the onomastic some might have been related (see Fig. 1: Ἀσιατικός son of Ἰάσων, brother of Δορζένθης; Δινίκενθος son of Βρινκάζερις, brother of Τήρης; Φλάβιος Σκέλης might have been the father of Φλάβιος Μουκαπορις).

Conclusions

This blog entry presented briefly some aspects related to the epigraphically attested population of Augusta Traiana, from the identified sample, to the identity markers and networks. While many of the inscriptions are laconic, or fragmentary, some are useful in reconstructing the profile of the population, the information on elite members being, as expected, the most comprehensive.