A post on the Creative Commons blog draws together four articles on the value of Creative Commons licensing for newspapers, scientists, film students, and Wikipedia “SEOers” respectively. All are worth reading, but it is the article on scientists that is of most interest here. This article, posted at ScienceBlogs on 1st May by Rob Knop makes the case that:

Scientists do not need, and indeed should not have, exclusive (or any) control over who can copy their papers, and who can make derivative works of their papers.

The very progress of science is based on derivative works! It is absolutely essential that somebody else who attempts to reproduce your experiment be able to publish results that you don’t like if those are the results they have. Standard copyright, however, gives the copyright holders of a paper at least a plausible legal basis on which to challenge the publication of a paper that attempts to reproduce the results— clearly a derivative work!

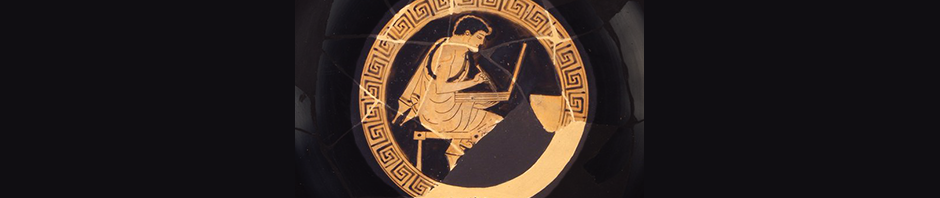

I would extend this argument (and indeed have done so repeatedly and vocally) to assert that this applies to equally to all academic research, including the Humanties. This is a key part of the philosophy behind the Open Source Critical Editions network that I helped convene last year. All published research includes the requirement to publish the “source code” (by way of citations, arguments, primary and secondary references, retraceable argumentation), and the expectation that others will use this “source” to verify, reproduce, modify, or refute your work. Copyright, and especially digital copyright and crippleware, should not be allowed to get in the way of this process because without this freedom a publication can not be considered research.

The author of the post at ScienceBlogs, who does not appear to be an attorney, seems to misunderstand what derivative works are supposed to protect. The derivative works protection covers things like translating a work into another language or adapting a book for the screen, etc.

As far as publishing another’s scientific results, that would be covered by 17 U.S.C. 102(b): “In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.”

A very interesting topic, more relevant to Stoa, is whether critical editions ought or ought not be considered a “derivative work” of the original ancient work. All the Qimron case in Israel said yes, the critical edition can be copyrighted, but most American commentators have criticized that opinion and its applicability to American copyright law.

Obviously, this is not legal advice, for that, you’d need to consult a competent attorney with whom you have an attorney-client relationship.

You have a good point, but–to be fair–there’s a difference between “supposed to protect” and “can be (ab)used to protect”. What is the DMCA supposed to protect? How many times has it be applied to protect someone from criticism, from parody, from citation; or even to try and blackmail out-of-court damages from somebody? It is important that a law not only be good “in spirit”, but expressed strongly and clearly so as to be immune from abuse in practice.

The copyright status of critical editions of classical texts is a vital question. Especially in a world where privileged papyrologists and epigraphers (for example–as the people most likely to come across “new” ancient texts) are conventionally given exclusive rights of first publication–and may hold onto that right for years. I’ve tried to have this issue addressed by a copyright lawyer on various occasions, but the answer always seems to be that it would have to be tested in a court. (All the potentially controversial cases I know of have been resolved amicably.)