By Lucy Yang (KCL)

| Texts aligned in Ugarit iAligner for this project: Satyricon 132.1, 132.2, 132.3, 132.4 |

The Satyricon by Petronius enjoys its modern reception as both a social satire to Neronian Rome, as most scholars believe its date to be, and as a pioneering example of the ancient novel. While the Satyricon’s content and form contribute to its fascination, they also complicate its translation, particularly in terms of preserving semiotic and structural integrity (Kay, Computational Linguistics, 1993). In terms of its contents, the Satyricon has had a reputation for its sexual explicitness and subversion rarely found in classical texts from the ‘classical canon’. Its fragmentary state and the nature of its content kept the Satyricon from a rightful examination as an ancient text, before its ‘scholarly worth’ was established by J.P. Sullivan in 1968 (The Satyricon of Petronius). Even then the Satyricon has continued to present interpretive challenges.

On the other hand, translation of the Satyricon to English is inherently a form of interpretation. I argue that translation of the Satyricon is especially important because it engages with the aspects of semiotic integrity and censorship, as demonstrated above, particularly relevant to the Satyricon. By studying translations, we get an insight of how the text is manipulated for an English-language readership. How is the form of the Satyricon mediated through translation, what has been presumed by the translation about the purpose of the text, how do different translations change the reader’s interpretation? Using text alignment to examine different translation intentions, this project evaluates how this digital tool may be applied in translation studies and Classical reception.

As Hardwick notes in her seminal 2000 book on translation theory and reception theory, Translating words, translating cultures, the main function of a translation of ancient texts is to provide ‘a contemporary means of understanding and responding to the ancient work’ (11-12). Translations offer a lens through which we can observe how a text was understood in different periods. The Satyricon was renowned for its ‘obscenity’ more so than its textual genius. This reputation often overshadowed its textual sophistication, leading to censorship through omission or alteration in translation (see Firebaugh 1922, below). The translations chosen for the project are more than 100 years apart, aiming to

demonstrate how the increased scholarly recognition has changed the ways in which the Satyricon is translated.

The two chosen translations are named A and B respectively. Translation A is by W. C. Firebaugh in 1922 (text from WikiSource). Translation B is by Gareth Schmeling, published by Loeb Classical Library in 2020. I have selected the Satyricon 132 for its moderate length to keep the project realisable and the conclusion more specific to textual analysis. Moreover, this passage incorporates both verse and prose—a prominent feature of the Satyricon ‘s form that makes it one of the few ancient novels. Content-wise, the passage includes features that contributed to the Satyricon’s early censorship as well as its later scholarly interest. It portrays both the ‘indecent’ element, Encolpius’ rage and shame over his sexual impotence and the literary aspect of the Satyricon’s intricate engagement with classical literary allusions (Conners, Petronius the Poet, 1998: 145; Rimell, Petronius and the Anatomy of Fiction, 2002). This project aims to demonstrate how digital textual alignment can highlight alterations and adaptations from Latin to English at both the formal and content levels. From evaluating the alignment’s ability to identify and display these differences, it aims to highlight how practicing textual alignment may help non-linguist classicists working mainly with translations to overcome the untranslatability of language barriers.

The methodology with translation alignment consists of the pairing of equivalence between the original text to the translated text(s), on word, phrase or sentence levels (Yousef and Janicke, Survey, 2021). General guidelines can be accessed on the community web site for different language pairings of original/translation. In practice, how and what to align can be project-specific. The guidelines for Latin-English alignment as provided by Valeria Irene Boano for Ugarit are mostly applied here. Most notably, this means aligning both the verb and its subject in English with the corresponding verb in Latin (Boano’s guidelines, 8.2). The Latin text and both translations are put through a single document to clean out the noise including page numbers and annotations, the punctuations are left in the text for an easier manual alignment process but not aligned. To keep a consistency for the alignment rate, definite and indefinite articles (‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’) are not aligned. Latin verbs that imply the subject are aligned with the subject in English when possible. This project evaluates interpretative integrity in different translations, reflecting the methodology of a non-linguist classicist with limited knowledge of the ancient language. To fulfil these needs, only words with direct semiotic correspondence are aligned with help from Latin-English dictionary.

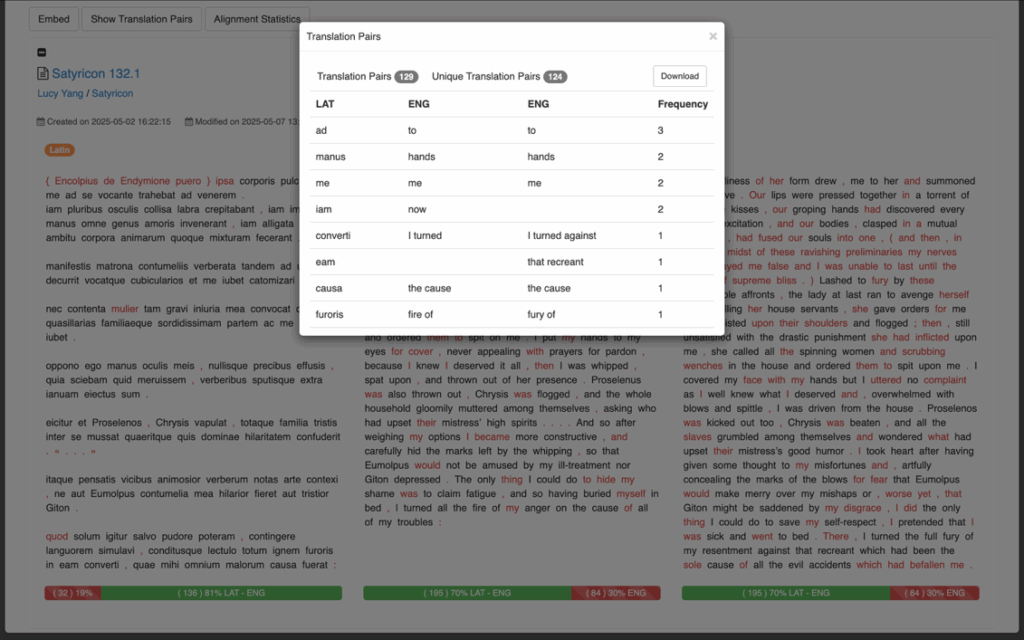

Graphic simulation makes the process of textual alignment efficiently interactive as it highlights the correspondence between texts (Yousef and Janicke, Survey, 2021). Ugarit provides a side-by-side view that gives immediate response to the aligned tokens for both editing and viewing (Yousef 2020). Ugarit also generates bar charts for statistics of alignment pairs, useful for an overview on the granularity of alignment (Fig. 1). For translation studies, the most useful may be the chart-view of aligned pairs, which provides a list to display how different translations render the same token from the original language, or the lack of direct correspondence i.e. omitted by the translation. The presence of alignment between only translations but without correspondence to the original text can be especially telling of the translation process, which will be discussed later.

Fig. 1: Table-view of translation pairs on Ugarit, downloadable data.

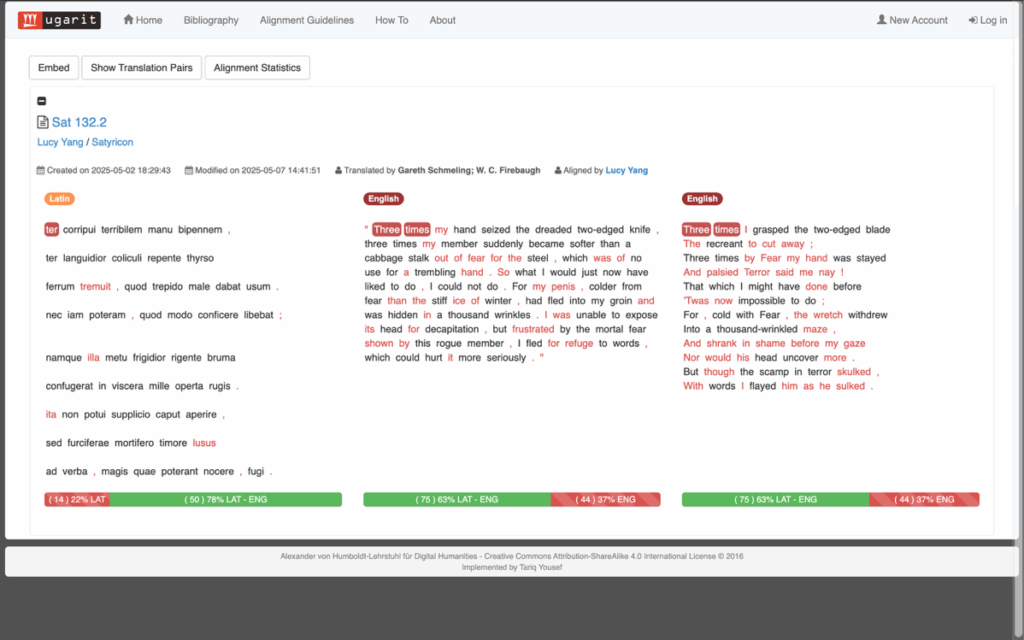

Doing text alignment provides an opportunity to review metrical composition otherwise hard to detect in an unknown language. The passage in question contains a verse section in Sotadean meter, which is an important formal observation as it adds a new layer to the complexity of the Satyricon’s embedded literary tradition. The Sotadean metre inverts the Homeric dactylic hexameters and is initially used for obscene or parodic verses, which gives more literary nuance to Sat. 132.2 (my alignment), as it gives an epic narrative to Encolpius’ failed castration in shame (Sapsford 2022, 3; 157). Both translations fail to capture the exact meter; but ancient metre getting lost in translation has been a long-term issue, that the compromise is taken as unavoidable (Crane et al. 2023, Beyond Translation, 170). While secondary literature may highlight the lost metre, in-text annotation that highlights syllables of different length works more efficiently, such as metric annotation for Homeric texts by David Chamberlain, though the annotated corpus is limitedly available. Translation alignment shows the correspondence intertextually between pairs, but this does not stand in for metrical data, though the visual correspondence to some extent highlights linguistic aspects such as the position of verbs which may have significance in the reader’s understanding of poetry (Fig. 2). However, despite its verse form, translation A has a much lower alignment rate than B. This may not be noticed without alignment because most imageries are kept intact in A (where all three texts are aligned) and provides the impression that both translations are as loyal to the original. But A invents and omits parts of the texts that undermines the textual integrity which the original Latin depends on to form intertextuality. By processing which Latin texts are aligned, the alignment highlights clearly which parts are translation’s invention or omission.

How does each translation process the question of the Satyricon’s form is a question even more relevant with the Satyricon’s non-verse sections. Translation alignment shows that, in the beginning of Sat. 132.1, translation B follows the parallelism in Latin, beginning with iam (now); but translation A abandons this structure and merges the actions into one continuous train of actions with ‘our’. This alteration may seem minor but though A keeps to the parallelism that begins each section of a sentence with the same word, the word is unaligned in Latin, suggesting that A put emphasis on contemporary readability that treats the Satyricon as a novel for entertainment. In contrast, Translation B is highlighted for a word-to-word approach as shown by the unaligned parts which are largely adverbs and subjects, already suggested or inflected in Latin.

However, unaligned texts, even adverbs and subjects, should not be all dismissed as simply semantic differences. Looking at the unaligned Latin words—Sat. 132.2: illa, singular ‘she’, is used to refer to Encolpius’ penis. The feminine pronoun holds significance in Roman semantic context but is missed in both translations. In Sat. 132.2, Translation A omits fugi (I fled), and its implication on the mutual cowardice in Encolpius and his genitals, which tweaks the dynamic of the mock-epic castration from self-shaming to a relentless pursuit to combat his impotence.

Fig. 2: Visualisation of alignment between original verse, non-verse translation and verse translation.

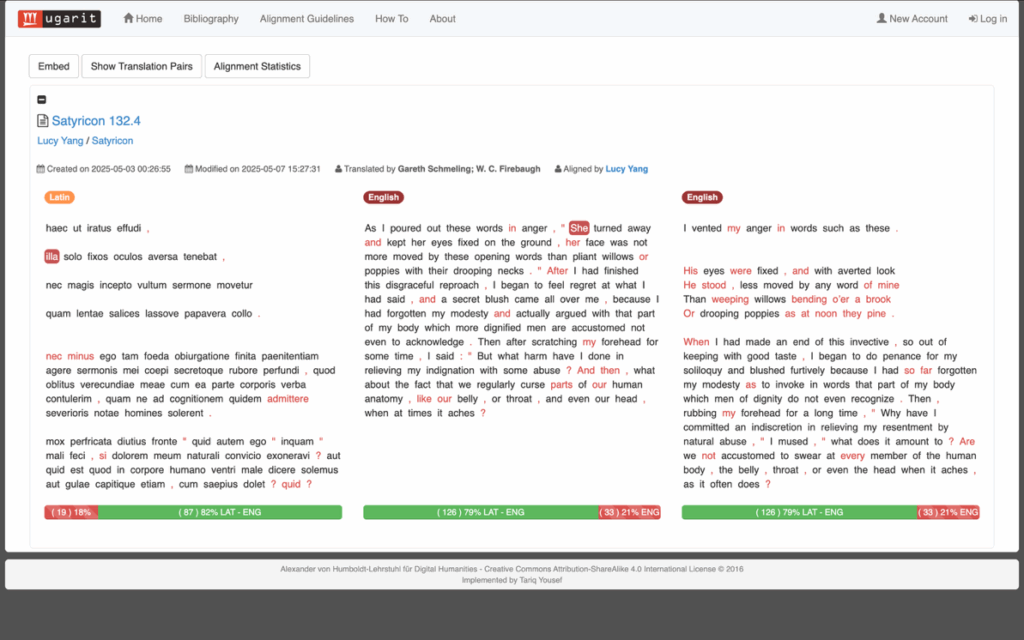

The side-by-side view between translations may reveal critical differences between versions. In the beginning of 132.4 (Fig. 3), translation A and B use opposite pronouns, one female (B) one male (A) for Encolpius’ penis, and they are carried on down the verse. Similarly, the word solo in 132.4 is understood as ‘soil’ in B and ignored in A, which alters the meaning. Translation A likely makes the change for the reason already argued: to make the text comprehensible in English, not so much to reflect the Latin semantics.

Translation B’s approach may be more efficient for non-Latinist classicists to work literary criticism with. However, words that rely on Latin’s inflected structure or carry meanings embedded in Latin literary semantics are still compromised in translation for the sake of coherence within English syntax and usage. The noun venereum has been translated to ‘make love’ (B) and ‘love’ (A), which are both semantically coherent but omit the evocation to Venus in Latin. In Sat. 132.3: furciferae is an altered form of the invective furcifer that’s commonly used on slaves, again, actively aligning the text may direct the reader to the untranslated servitude imposed with invective. In Sat. 132.1, catomizari is an unusual conjugation for catomidio that cannot be found in Latin online dictionaries. Both translations give it the exact wording ‘hoisted and flogged’. During the alignment, the curious absence of the word from dictionaries may direct the reader to secondary literature, which would lead the discourse on multiple versions of Latin texts, raising awareness to annotations for Latin that may otherwise not be as significant to a non-Latinist’s knowledge.

Fig. 3: The presence and absence of the feminine pronoun, highlighted.

By practicing active translation alignment, one is naturally drawn to the challenges. As demonstrated above, unaligned text or contradicting meanings between translations often flag the ‘untranslatability’ and directs to more in-depth understandings. Between alignment of translations, we may also learn about which ‘original’ text each translator works from. The end of 132.3, according to Loeb’s Latin is ‘rogo te, mihi apodixin « non » defunctoriam redde’. Alignment indicates a level of correspondence with both translations but conveying very different meanings: A asking for ‘sign…however faint’ and B for ‘serious proof’. It suggests that the two translations may be using different Latin texts, especially with the ambiguous addition of ‘« non »’. As made identifiable by the list of translation pairs, Sat. 132.4 has alignment occurring only between translations: ‘words’ is included for translations but not found in Latin. It may suggest cross-referencing between the later to the earlier version, or the same translation convention has been used.

My project conducts a practical manual translation alignment with an ancient text and two temporally distant translations, in evaluation of how active alignment can assist with what would have been the persistent issue of untranslatability for people without knowledge of the ancient language(s). While demonstrating that the 2020 translations have an emphasis on conveying meanings as exact as possible, as coherent to the scholarly recognition of the Satyricon, the 1922 translation prioritises the Satyricon as both entertaining and equivalent to a modern novel. The experience of manually aligning the texts is proven useful for a non-linguist to give a more semantically inherent—a sense of lingual ‘nativeness’—analysis to their unknown languages. From the interactive alignment practice aided by immediate visual response, both aligned and unaligned texts are useful for discussions. The alignment rate tells more nuance than how literate the translation is to the original. By doing active alignment, the user can efficiently spot addition and omission in translations, both in form and content, including specific tokens to detect translational aspect such as censorship. Furthermore, vast difference between translations could imply different versions of ‘original’ texts being used, directing attention to the manuscripts where the Latin texts are sourced, an aspect not often addressed by publications of translations. Including alignment as part of the literary analysis can redirect non-linguists to research for secondary annotation and literature, as alignment flags up specification that helps to direct their search in an otherwise convoluted. While doing manual alignment gives the advantage of promoting a highly focused interaction with the text, its time-consuming nature deems it more suitable for shorter passages. For longer or entire-work alignment, there are pre-aligned versions for canons such as Homer, and auto-alignment tools, such as the Ugarit auto-aligner to conduct the work for the others. As important and information-rich as the overview on alignment data is, having first-person experience with manual alignment is both a methodology to evaluate translation and a gateway to further research that gives great nuance to the data.