Through the Roman Society Museum and Heritage Summer Placement, I was chosen to participate in a two week long internship with the Hellenic and Roman Library and the Institute of Classical Studies, at the University of London. My time here was spent cataloguing and 3D modelling the Ehrenberg Collection, which consists of Greek and Roman artifacts from various periods that were donated to the library by Victor Ehrenberg.

This placement interested and benefited me as a Master’s student in Digital Archaeology and Heritage Management. I will soon be completing my degree at Leiden University, where I have been researching the uses, politics and ethics of 3D imaging as a documentation tool for tangible heritage that will be repatriated to its origin communities, or for items that are difficult for researchers and the public to access.

Working with the Ehrenberg collection was an interesting addition to my research, because the goal of the project was to make the items fully accessible online. When Victor Ehrenberg donated these items, he wished they would be used for further research and education, and thanks to 3D imaging, we are now able to make the artifacts accessible for those interested to view and learn from without having to request them from the library. Furthermore, many of the items are still being held in storage either due to their fragility or lack of display room in the library, so making them available to view digitally will hopefully help carry out Ehrenberg’s wishes and benefit researchers of Greek and Roman antiquity.

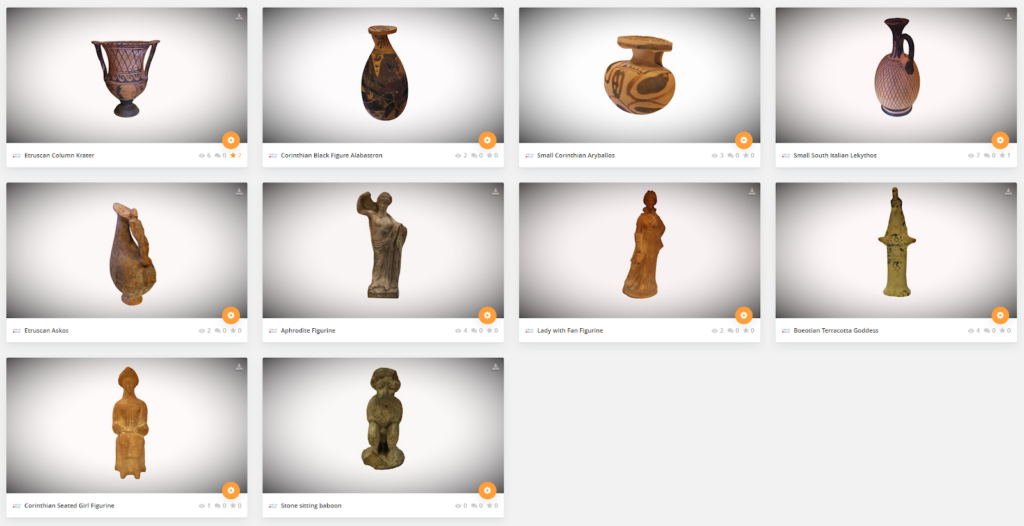

3D models that are now available on Sketchfab.

During this internship, I identified and transcribed Ehrenberg’s original catalogue of artifacts into an online catalogue, which will eventually be added to the library’s database. I then began creating 3D models of the items on Agisoft Photoscan, a photogrammetric software. The models that have been created are now accessible on Sketchfab to view and download for free at https://sketchfab.com/icsehrenberg or https://sketchfab.com/awalsh/collections/harl-ehrenberg. While completing these steps, I also created a workflow with useful tips and tricks so that this project may be continued in the future by following the same methodology. This includes a standard workflow for taking photos and using Agisoft, creating a 360 degree model and uploading the completed models to Sketchfab.

A variety of challenges arose during this project. The first step was identifying and transcribing the items in the original catalogue, which contained only a brief description of the items in the collection. Perhaps with future research of these items, they will be assigned more descriptive identifies that can be included in the archive.

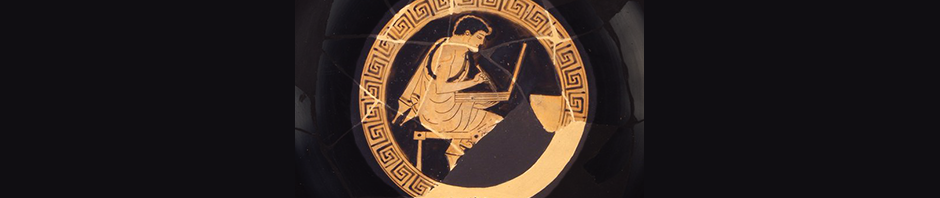

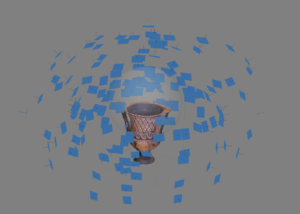

The 3D models were created using photogrammetry with Agisoft Photoscan Pro. Of the almost 200 items in the collection, 10 models were created and uploaded to Sketchfab. The photos were taken using a Canon Rebel t5i with varying settings depending on the item, but usually with an ISO of 3200, an aperture of F/9 and shutter speed of 1/30. The items were placed on a stable surface while I moved the camera around it, taking multiple rounds of photos at different heights, always at 70-80% overlap. The photos were always immediately added and aligned on Agisoft Photoscan at a low quality setting to ensure a sufficient amount of camera coverage before the item was moved. In many cases, I went back and took additional photos, particularly when the item such as a jug included a handle, as a significant amount of photos were needed to capture around the handle and between the handle and neck of the vessel. The amount of photos taken were between 75-135, depending on the size of the object. Some items were particularly difficult to capture, such as the painted column krater due to its curved dark interior (for which I used the camera’s flash), and with a small red figure aryballesque lekythos, which was not modelled in the end due to the difficulty it presented having a reflective surface, and due to time constraints.

Camera alignment on Agisoft Photoscan while modelling a krater.

Once an appropriate amount of cameras aligned on a high quality setting, I proceeded with creating the dense point cloud, mesh, and texture usually using Photoscan’s default parameters. The bases of most of the items were not photographed or rendered on Photoscan because there usually was nothing of interest. In these cases, I used MeshMixer to create a flat base and filled it using a similar texture as the rest of the model. This program was also useful for closing holes that were missed in the mesh. However, there were a few items that had painted bases and were therefore necessary to capture. In these cases, I took photos of the item sitting upright, then flipped it upside down and repeated the photography. The photos were then divided into two chunks on Photoscan and automatically aligned using the align chunks and merge chunks tools. This method did create a messier dense cloud and more time was spent cleaning the cloud and aligning the two clouds, but it was worth the effort in the end to create a 360 degree view of the object.

A very exciting aspect of this project was being taught how to 3D print an item. After creating a 3D model from the original that was kept in storage, we printed a copy of a Roman Egyptian stone baboon. 3D printing is a useful method of making artifacts accessible, because they can be used as teaching tools or if the original item is too fragile to handle. Likewise, some items in the collection were broken and are in need of repair, but by 3D modelling the fragments together, I was able to “digitally repair” them so they are visible as they originally looked. For example, two goddess figurines had their heads detached, and a large column krater had a broken handle. In their 3D models you can see them reattached.

3D printing a Roman Egyptian Baboon.

Figuring out how to include in the archive Ehrenberg’s drawings and photographs, as well as the 3D models that will eventually be created of all the items has not yet been decided. With such a large data set that the models created, consideration about how to store this data is an important issue. The ten models that were made created a data set of approximately 50GB, for which a data repository will eventually have to be built. When all the items are eventually modelled, this repository could make up close to 1TB of data.

I enjoyed working with the items in this collection because it gave me an amazing opportunity to continue learning about 3D imaging and its valuable uses. Being at the HARL for two weeks showed me what a valuable resource it is to academics in the field, and I hope my contribution to the Institute through this project proves useful. Thank you to Fiona Haarer at the Roman Society, and to Gabriel Bodard, Joanna Ashe and Valeria Vitale at the ICS for their help with planning and offering their advice and expertise on this project.